# A slow tour through Mu software on x86 computers

[Mu](https://github.com/akkartik/mu) shrinks all the software in a computer

until it can (in principle) fit in a single head. Sensible error messages with

as little code as possible, starting all the way from your (x86) processor's

instruction set. Everything easy to change to your needs

([habitable](http://akkartik.name/post/habitability)), everything easy to

check up on ([auditable](http://akkartik.name/post/neighborhood)).

This page is a guided tour through [Mu's Readme](https://github.com/akkartik/mu)

and reference documentation. We'll start out really slow and gradually

accelerate as we build up skills. By the end of it all, I hope you'll be able

to program your processor to run some small graphical programs. The programs

will only use a small subset of your computer's capabilities; there's still a

lot I don't know and therefore cannot teach. However, the programs will run on

a _real_ processor without needing any other intermediary software.

_Prerequisites_

You will need:

* A computer with an x86 processor running Linux. Mu is designed to eventually

escape Linux, but still needs some _host_ environment for now. Other

platforms will also do (BSD, Mac OS, Windows Subsystem for Linux), but be

warned that things will be _much_ (~20x) slower.

* Some fluency in typing commands at the terminal and interpreting their

output.

* Fluency with some text editor. Things like undo, copying and pasting text,

and saving work in files. A little experience programming in _some_ language

is also handy.

* [Git](https://git-scm.com) for version control.

* [QEMU](https://www.qemu.org) for emulating a processor without Linux.

* Basic knowledge of number bases, and the difference between decimal and

hexadecimal numbers.

* Basic knowledge of the inside of a processor, such as the difference between

a small number of registers and a large number of locations in memory.

If you have trouble with any of this, [I'm always nearby and available to

answer questions](http://akkartik.name/contact). The prerequisites are just

things I haven't figured out how to explain yet. In particular, I want this

page to be accessible to people who are in the process of learning

programming, but I'm sure it isn't good enough yet for that. Ask me questions

and help me improve it.

## Task 1: getting started

Read the first half of [the Readme](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/README.md)

(stop before the section on “Syntax”). Can you figure out the

commands to prepare Mu on your computer?

Open a terminal and run the following commands to prepare Mu on your computer:

```

git clone https://github.com/akkartik/mu

cd mu

```

Run a small program to start:

```

./translate tutorial/task1.mu

qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

If you aren't on Linux (or Windows Subsystem for Linux), the command for

creating `code.img` will be slightly different:

```

./translate_emulated tutorial/task1.mu

qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

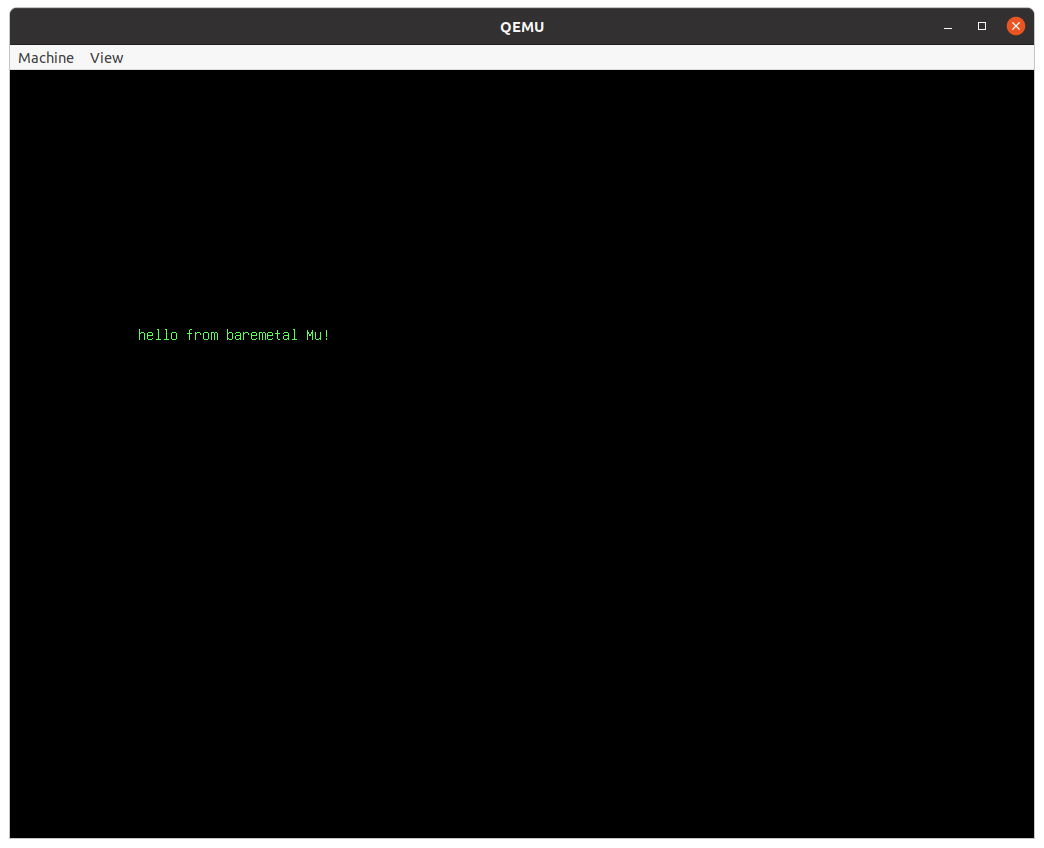

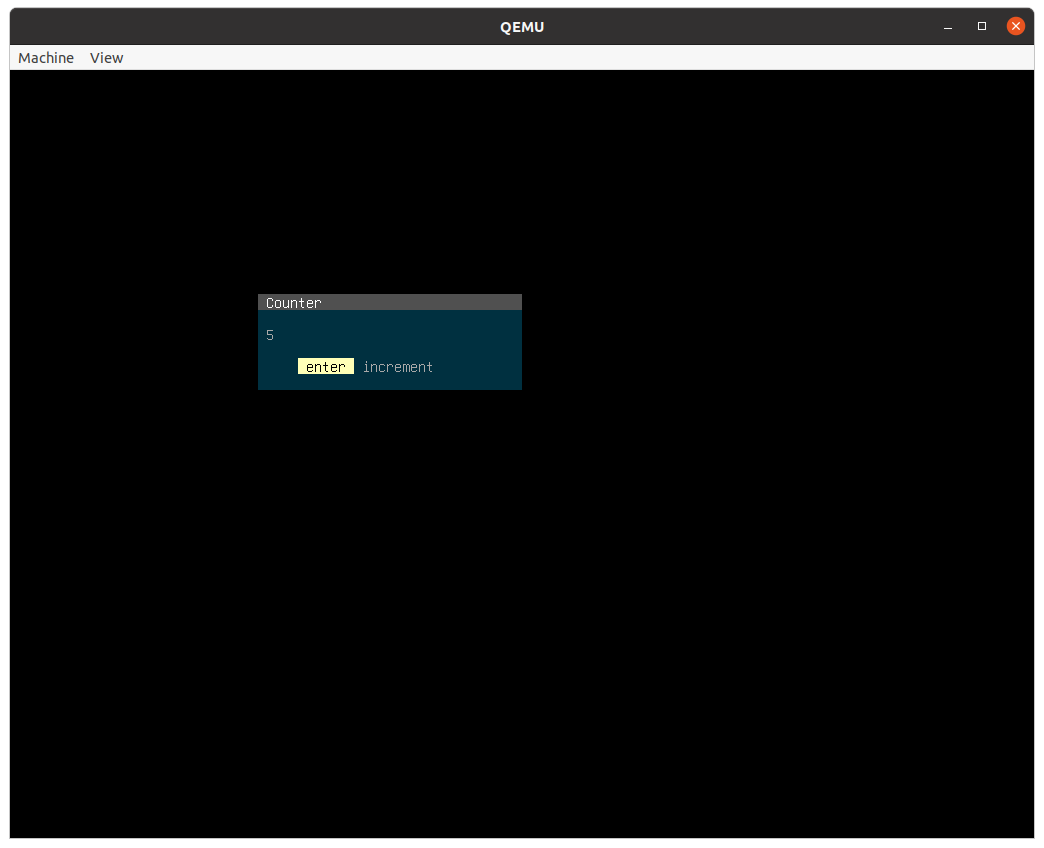

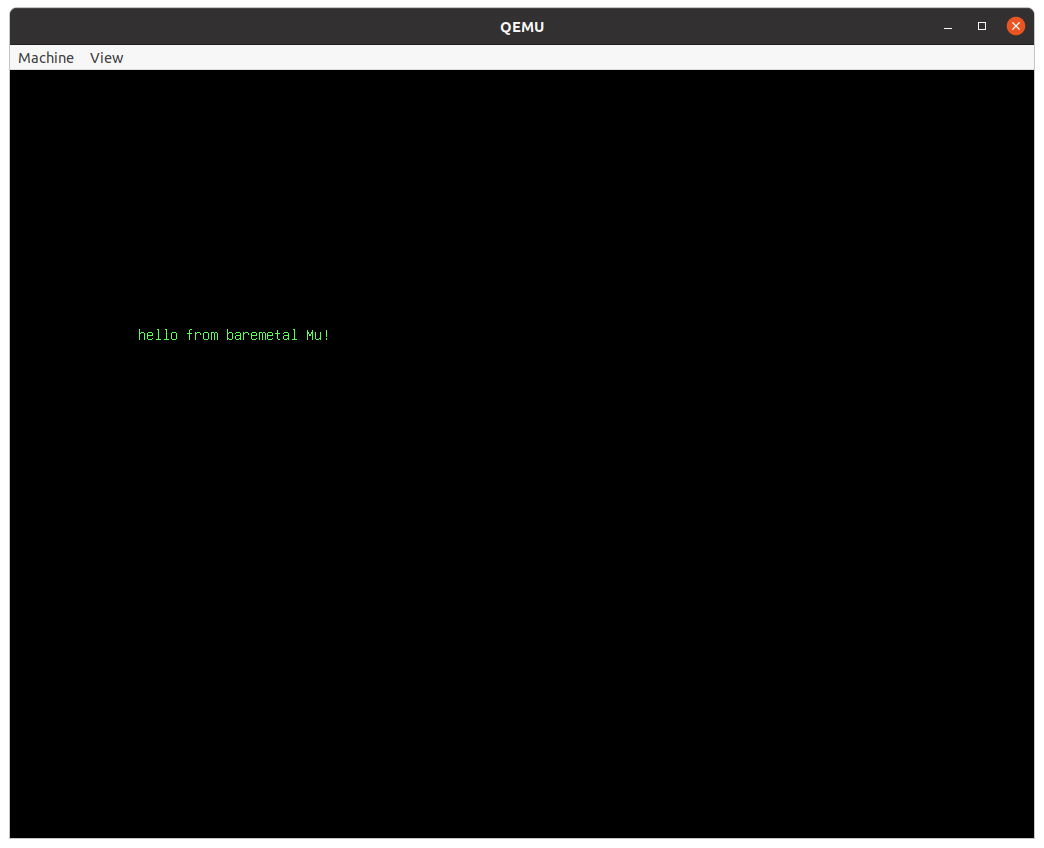

Either way, you should see this:

If you have any trouble at this point, don't waste _any_ time thinking about

it. Just [get in touch](http://akkartik.name/contact).

(You can look at `tutorial/task1.mu` at this point if you like. It's just 3

lines long. But don't worry if it doesn't make much sense.)

## Task 2: running automated tests

Here's a new program to run:

```

./translate tutorial/task2.mu

qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

(As before, I'll leave you to substitute `translate` with `translate_emulated`

if you're not on Linux.)

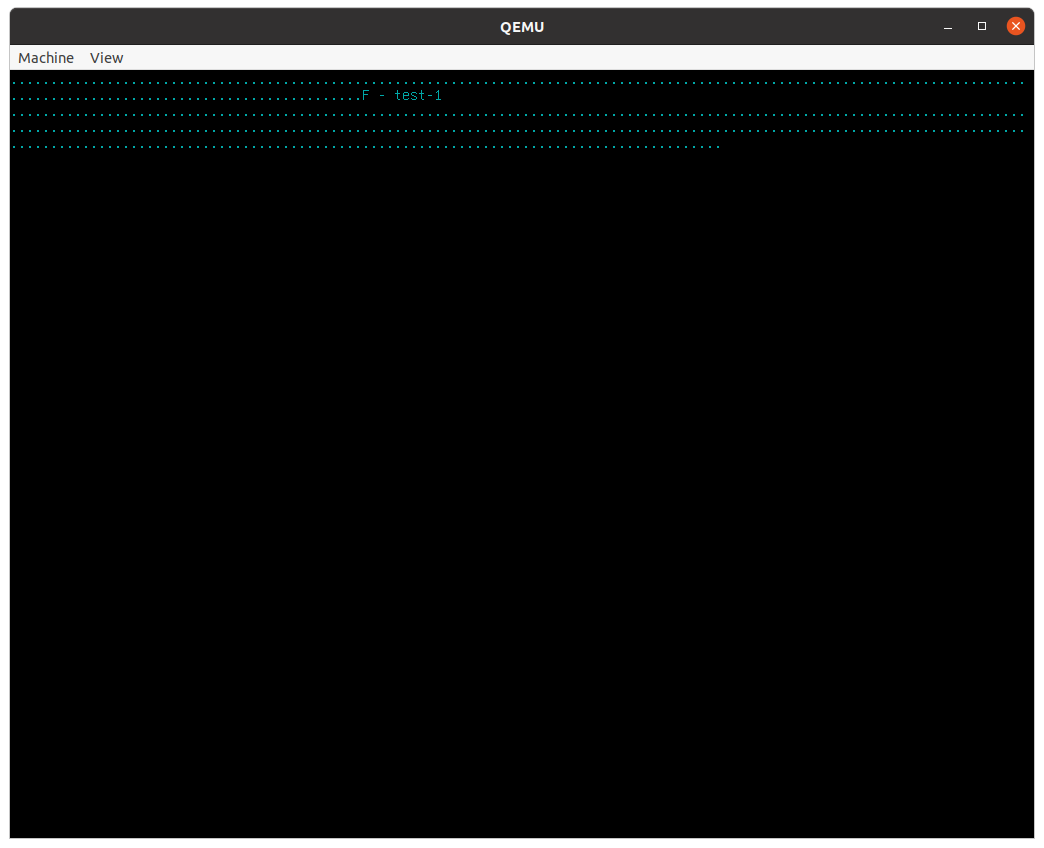

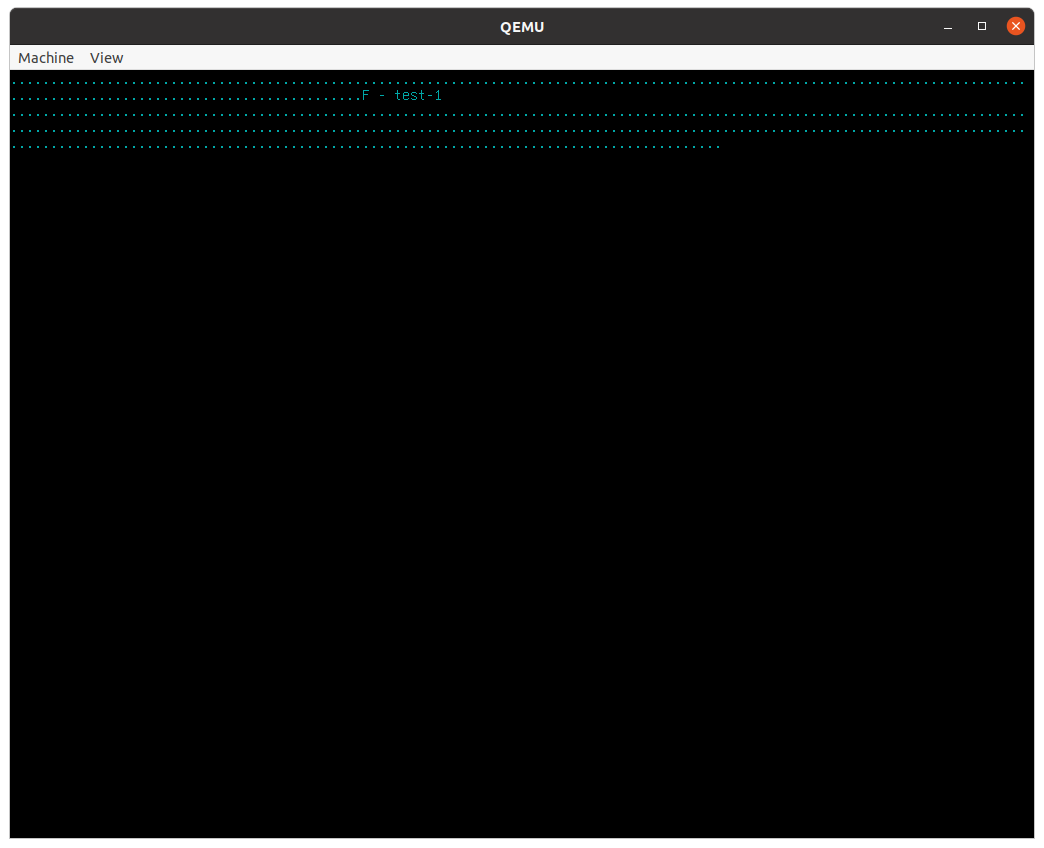

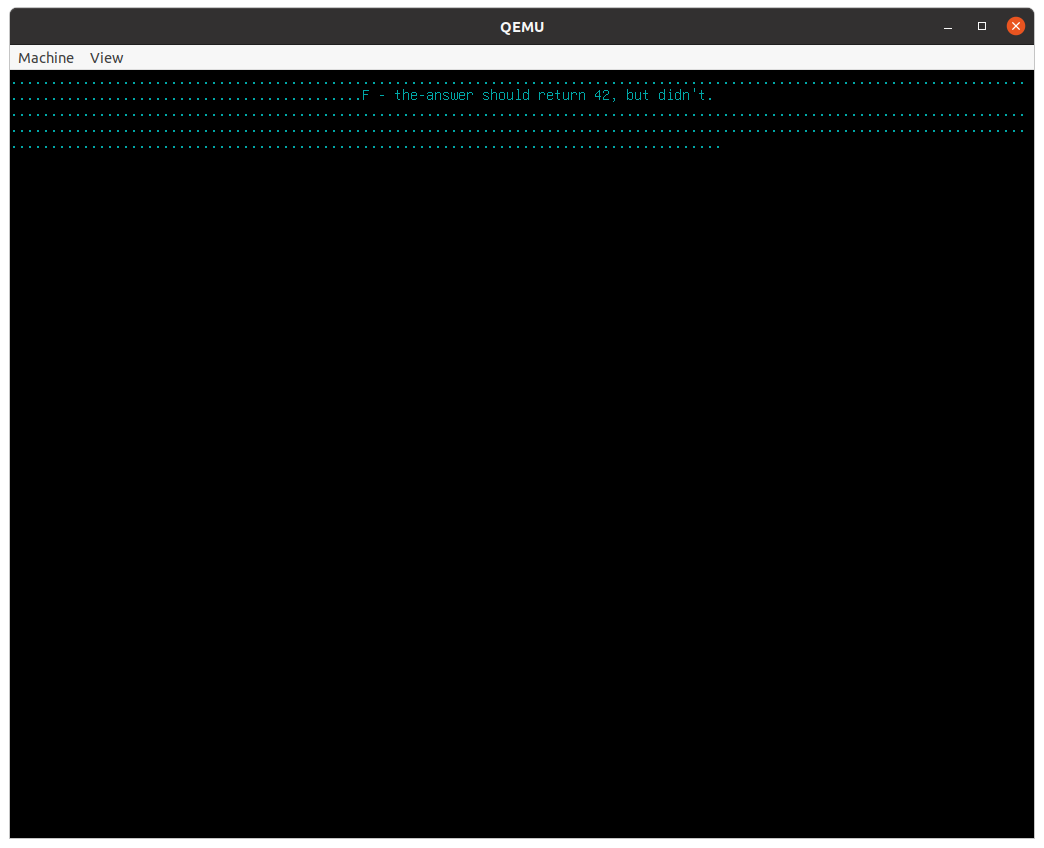

This time the screen will look like this:

If you have any trouble at this point, don't waste _any_ time thinking about

it. Just [get in touch](http://akkartik.name/contact).

(You can look at `tutorial/task1.mu` at this point if you like. It's just 3

lines long. But don't worry if it doesn't make much sense.)

## Task 2: running automated tests

Here's a new program to run:

```

./translate tutorial/task2.mu

qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

(As before, I'll leave you to substitute `translate` with `translate_emulated`

if you're not on Linux.)

This time the screen will look like this:

Each of the dots represents an automated _test_, a little self-contained and

automated program run and its results verified. Mu comes with a lot of tests

(every function starting with 'test-' is a test), and it always runs all tests

on boot before it runs any program. You may have missed the dots when you ran

Task 1 because there were no failures. They were printed on the screen and

then immediately erased. In Task 2, however, we've deliberately included a

failing test. When any tests fail, Mu will immediately stop, showing you

messages from failing tests and implicitly asking you to first fix them. A lot

of learning programming is about building a sense for when you need to write

tests for the code you write.

(Don't worry just yet about what the message in the middle of all the dots means.)

## Task 3: configure your text editor

So far we haven't used a text editor yet, but we will now be starting to do

so. Before we do, it's worth spending a little bit of time setting your

preferred editor up to be a little more ergonomic. Mu comes with _syntax

highlighting_ settings for a few common text editors in the `editor/`

sub-directory. If you don't see your text editor there, or if you don't know

what to do with those files, [get in touch!](http://akkartik.name/contact)

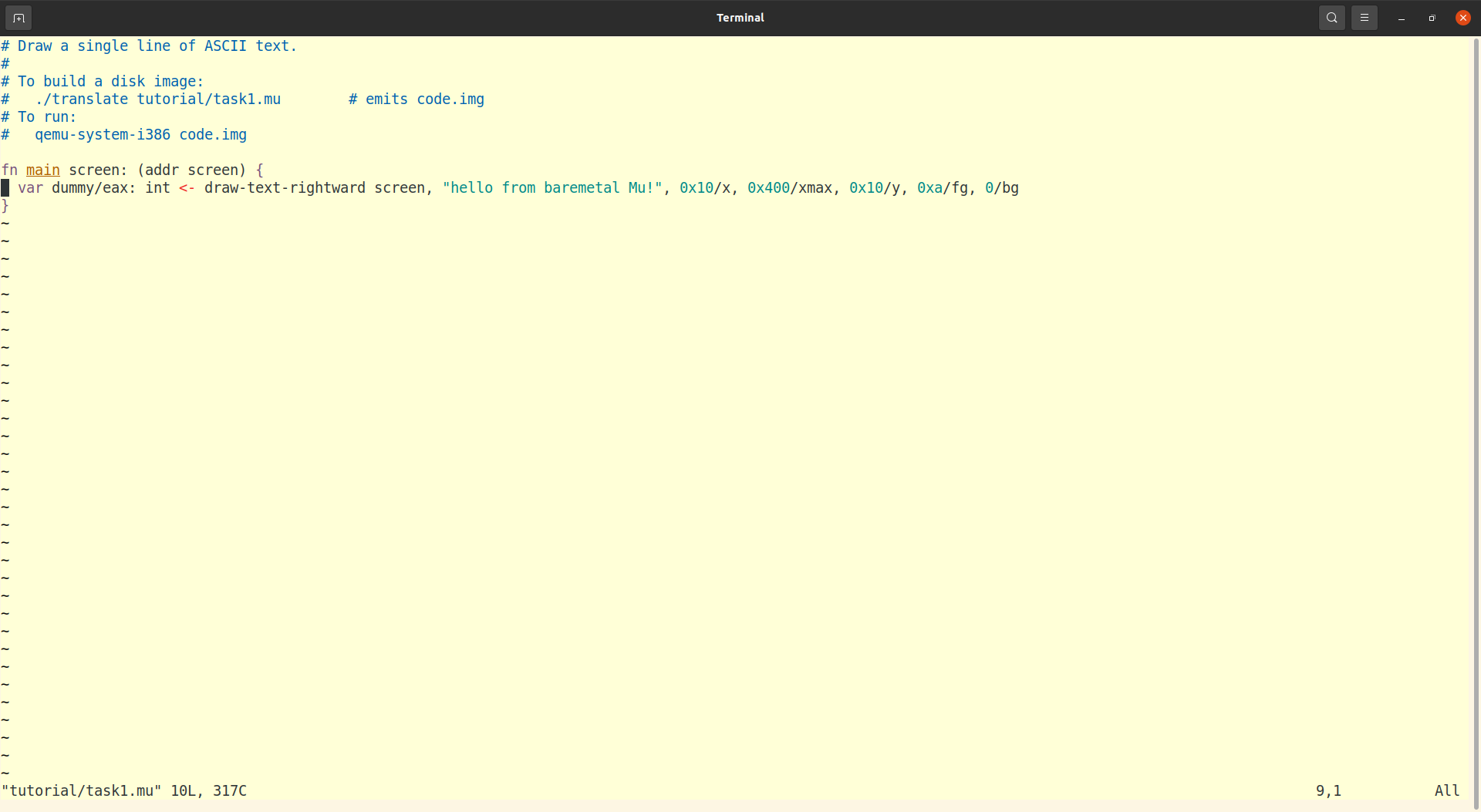

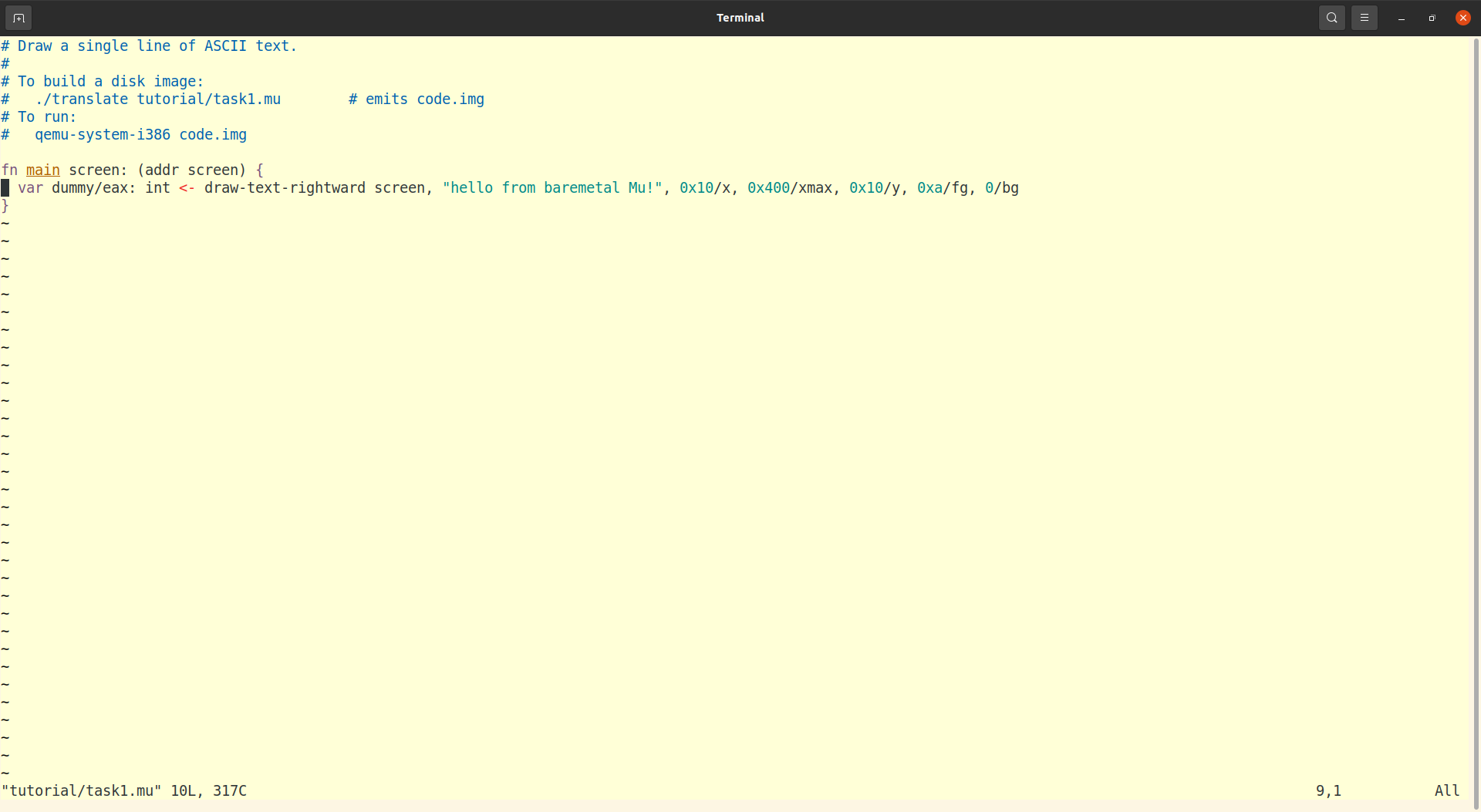

Here's what my editor (Vim) looks like with these settings on the program of

Task 1:

Each of the dots represents an automated _test_, a little self-contained and

automated program run and its results verified. Mu comes with a lot of tests

(every function starting with 'test-' is a test), and it always runs all tests

on boot before it runs any program. You may have missed the dots when you ran

Task 1 because there were no failures. They were printed on the screen and

then immediately erased. In Task 2, however, we've deliberately included a

failing test. When any tests fail, Mu will immediately stop, showing you

messages from failing tests and implicitly asking you to first fix them. A lot

of learning programming is about building a sense for when you need to write

tests for the code you write.

(Don't worry just yet about what the message in the middle of all the dots means.)

## Task 3: configure your text editor

So far we haven't used a text editor yet, but we will now be starting to do

so. Before we do, it's worth spending a little bit of time setting your

preferred editor up to be a little more ergonomic. Mu comes with _syntax

highlighting_ settings for a few common text editors in the `editor/`

sub-directory. If you don't see your text editor there, or if you don't know

what to do with those files, [get in touch!](http://akkartik.name/contact)

Here's what my editor (Vim) looks like with these settings on the program of

Task 1:

It's particularly useful to highlight _comments_ which the computer ignores

(everything on a line after a `#` character) and _strings_ within `""` double

quotes.

## Task 4: your first Mu statement

Mu is a statement-oriented language. Most statements translate into a single

instruction to the x86 processor. Quickly read the first two sections of the

[Mu reference](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md) (about

functions and variables) to learn a little bit about it. It's ok if it doesn't

all make sense just yet. We'll reread it later.

Here's a skeleton of a Mu function that's missing a single statement.

```

fn the-answer -> _/eax: int {

var result/eax: int <- copy 0

# insert your statement below {

# }

return result

}

```

Try running it now:

```

./translate tutorial/task4.mu

qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

(As before, I'll leave you to substitute `translate` with `translate_emulated`

if you're not on Linux.)

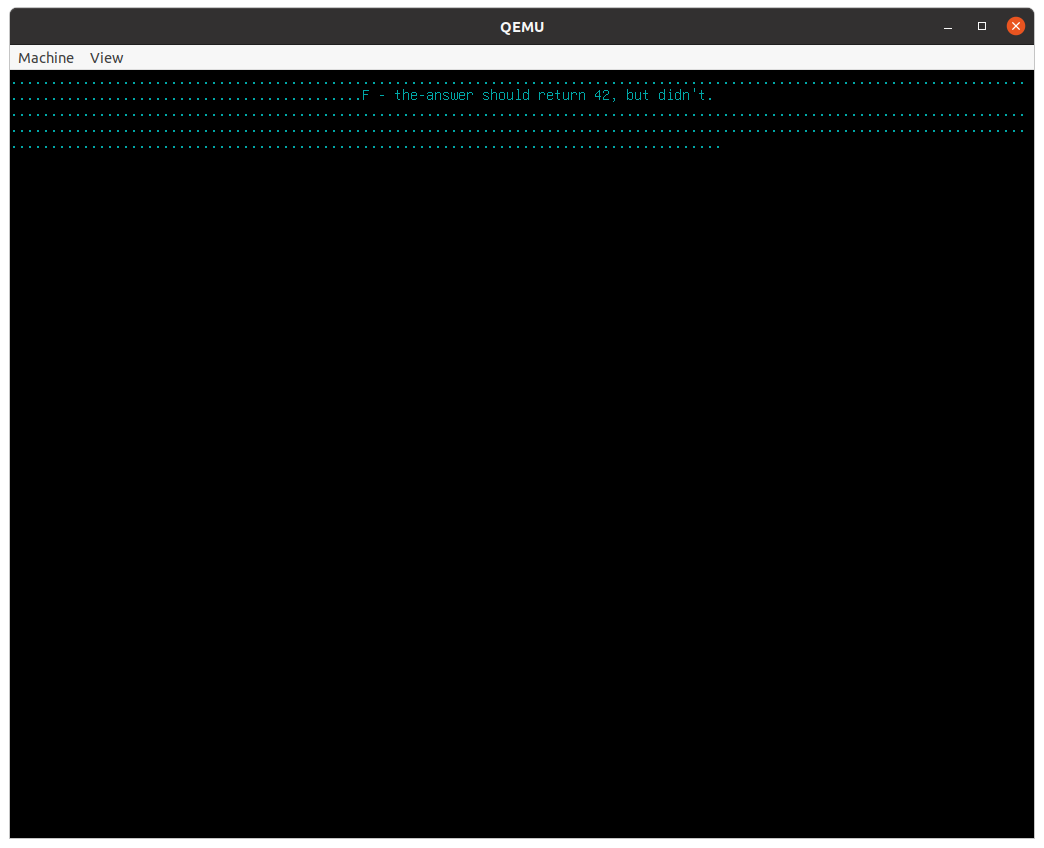

You should see a failing test that looks something like this:

It's particularly useful to highlight _comments_ which the computer ignores

(everything on a line after a `#` character) and _strings_ within `""` double

quotes.

## Task 4: your first Mu statement

Mu is a statement-oriented language. Most statements translate into a single

instruction to the x86 processor. Quickly read the first two sections of the

[Mu reference](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md) (about

functions and variables) to learn a little bit about it. It's ok if it doesn't

all make sense just yet. We'll reread it later.

Here's a skeleton of a Mu function that's missing a single statement.

```

fn the-answer -> _/eax: int {

var result/eax: int <- copy 0

# insert your statement below {

# }

return result

}

```

Try running it now:

```

./translate tutorial/task4.mu

qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

(As before, I'll leave you to substitute `translate` with `translate_emulated`

if you're not on Linux.)

You should see a failing test that looks something like this:

Open `tutorial/task4.mu` in your text editor. Think about how to add a line

between the `{}` lines to make `the-answer` return 42. Rerun the above

commands. You'll know you got it right when all the tests pass, i.e. when the

rows of dots and text above are replaced by an empty screen.

Don't be afraid to run the above commands over and over again as you try out

different solutions. Here's a way to run them together so they're easy to

repeat.

```

./translate tutorial/task4.mu && qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

In programming there is no penalty for making mistakes, and once you arrive at

the correct solution you have it forever. As always, [feel free to ping me and

ask questions or share your experience](http://akkartik.name/contact).

Mu statements can have _outputs_ on the left (before the `<-`) and _inouts_

(either inputs or outputs) on the right, after the instruction name. The order

matters.

One gotcha to keep in mind is that numbers in Mu must always be in hexadecimal

notation, starting with `0x`. Use a calculator on your computer or phone to

convert 42 to hexadecimal, or [this page on your web browser](http://akkartik.github.io/mu/tutorial/converter.html).

## Task 5: variables in registers, variables in memory

We'll now practice managing one variable in a register (like last time) and

a second one in memory. To prepare for this, reread the first two sections of

the [Mu reference](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md). The

section on [integer arithmetic](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#integer-arithmetic)

also provides a useful cheatsheet of the different forms of instructions you

will need.

Here's the exercise, with comments starting with `#` highlighting the gaps in

the program:

```

fn foo -> _/eax: int {

var x: int

# statement 1: store 3 in x

# statement 2: define a new variable 'y' in register eax and store 4 in it

# statement 3: add y to x, storing the result in x

return x

}

```

Again, you're encouraged to repeatedly try out your programs by running this

command as often as you like:

```

./translate tutorial/task5.mu && qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

The section on [integer arithmetic](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#integer-arithmetic)

shows that Mu consistently follows a few rules:

* Instructions that write to a register always have an output before the `<-`.

* Instructions that use an argument in memory always have it as the first

inout.

* Instructions that write to memory have a preposition in their name. Contrast

`add` to a register vs `add-to` a memory location, `subtract` from a

register vs `subtract-from` a memory location, and so on.

If you're stuck, as always, [my door is open](http://akkartik.name/contact).

You can also see a solution in the repository, though I won't link to it lest

it encourage peeking.

Where possible, try to store variables in registers rather than the stack. The

two main reasons to use the stack are:

* when you need lots of variables and run out of registers, and

* when you have types that don't fit in 32 bits.

## Task 6: getting used to a few error messages

If you're like me, seeing an error message can feel a bit stressful. It

usually happens when you're trying to get somewhere, it can feel like the

computer is being deliberately obtrusive, there's uncertainty about what's

wrong.

Well, I'd like to share one trick I recently learned to stop fearing error

messages: deliberately trigger them at a time and place of your choosing, when

you're mentally prepared to see them. That takes the stress right out.

Here's the skeleton for `tutorial/task6.mu`:

```

fn main {

var m: int

var r/edx: int <- copy 0

# insert a single statement below

}

```

(Reminder: `m` here is stored somewhere in memory, while `r` is stored in

register `edx`. Variables in registers must always be initialized when they're

created. Variables in memory must never be initialized, because they're always

implicitly initialized to 0.)

Now, starting from this skeleton, type the following statements in, one at a

time. Your program should only ever have one more statement than the above

skeleton. We'll try out the following statements, one by one:

* `m <- copy 3`

* `r <- copy 3`

* `copy-to r, 3`

* `copy-to m, 3`

Before typing in each one, write down whether you expect an error. After

trying it out, compare your answer. It can also be useful to write down the

exact error you see, and what it means, in your own words.

(Also, don't forget to delete the statement you typed in before you move on to

trying out the next one.)

Making notes about error messages is an example of a more general trick called

a [runbook](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Runbook). Runbooks are aids to

memory, scripts for what to do when you run into a problem. People think worse

in the presence of stress, and runbooks can help reduce the need for thinking

in the presence of stress. They're a way of programming people (your future

self or others) rather than computers.

## Task 7: variables in registers, variables in memory (again)

Go back to your program in Task 5. Replace the first statement declaring

variable `x`:

```

var x: int

```

so it looks like this:

```

var x/edx: int <- copy 0

```

Run `translate` (or `translate_emulated`) as usual. Use your runbook from Task

6 to address the errors that arise.

## Task 8: primitive statements vs function calls

Managing variables in memory vs register is one of two key skills to

programming in Mu. The second key skill is calling primitives (which are

provided by the x86 instruction set) vs functions (which are defined in terms

of primitives).

To prepare for this task, reread the very first section of the Mu reference,

on [functions and function calls](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#functions).

Now look at the following programs. In each case, write down whether you

expect translation to return any errors and why.

```

fn f a: int {

}

fn main {

f 0

var r/eax: int <- copy 3

f r

var m: int

f m

}

```

(When you're ready, try the above program out as `./translate tutorial/task8a.mu`.)

```

fn f -> _/eax: int {

var result/ecx: int <- copy 0

return result

}

fn main {

var x/eax: int <- f

}

```

(When you're ready, try the above program out as `./translate tutorial/task8b.mu`.)

```

fn f -> _/eax: int {

return 3

}

fn main {

var x/ecx: int <- f

}

```

(When you're ready, try the above program out as `./translate tutorial/task8c.mu`.)

Functions have fewer restrictions than primitives on inouts, but more

restrictions on outputs. Inouts can be registers, or memory, or even literals.

This is why the first example above is legal. Outputs, however, _must_

hard-code specific registers, and function calls must write their outputs to

matching registers. This is why the third example above is illegal.

One subtlety here is that we only require agreement on output registers

between function call and function header. We don't actually have to `return`

the precise register a function header specifies. The return value can even be

a literal integer or in memory somewhere. The `return` is really just a `copy`

to the appropriate register(s). This is why the second example above is legal.

## Task 9: juggling registers between function calls

Here's a program:

```

fn f -> _/eax: int {

return 2

}

fn g -> _/eax: int {

return 3

}

fn add-f-and-g -> _/eax: int {

var x/eax: int <- f

var y/eax: int <- g

x <- add y

return x

}

```

What's wrong with this program? How can you fix it and pass all tests by

modifying just function `add-f-and-g`?

By convention, most functions in Mu return their results in register `eax`.

That creates a fair bit of contention for this register, and we often end up

having to move the output of a function call around to some other location to

free up space for the next function we need to call.

An alternative approach would be to distribute the load between registers so

that different functions use different output registers. That would reduce the

odds of conflict, but not eradicate them entirely. It would also add some

difficulty in calling functions; now you have to remember what register they

write their outputs to. It's unclear if the benefits of this alternative

outweigh the costs, so Mu follows long-established conventions in other

Assembly languages. I do, however, violate the `eax` convention in some cases

where a helper function is only narrowly useful in a single sort of

circumstance and registers are at a premium. See, for example, the definition

of the helper `_read-dithering-error` [when rendering images](http://akkartik.github.io/mu/html/511image.mu.html).

The leading underscore indicates that it's an internal detail of

`render-image`, and not really intended to be called by itself.

## Task 10: operating with fractional numbers

All our variables so far have had type `int` (integer), but there are limits

to what you can do with just whole integers. For example, here's the formula

a visitor to the US will require to convert distances mentioned on road signs

from miles to kilometers:

```

distance * 1.609

```

Write a function to perform this conversion. Some starting points:

* Reread [the section on variables and registers](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#variables-registers-and-memory)

with special attention to the `float` type.

* Read [the section on fractional arithmetic](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#fractional-arithmetic).

* One wrinkle is that the x86 instruction set doesn't permit literal

fractional arguments. So you'll need to _create_ 1.609 somehow. See the

section on moving values around under [operations on simple types](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#operations-on-simple-types).

This task has four source files in the repo that reveal more and more of the

answer. Start from the first, and bump down if you need a hint.

* tutorial/task10.mu

* tutorial/task10-hint1.mu

* tutorial/task10-hint2.mu

* tutorial/task10-hint3.mu

## Task 11: conditionally executing statements

Here's a fragment of Mu code:

```

{

compare x, 0

break-if->=

x <- copy 0

}

```

The combination of `compare` and `break` results in the variable `x` being

assigned 0 _if and only if_ its value was less than 0 at the beginning. The

`break` family of instructions is used to jump to the end of an enclosing `{}`

block if some condition is satisfied, skipping all intervening instructions.

To prepare for this task, read the sections in the Mu reference on

[`compare`](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#comparing-values)

and [branches](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#branches).

Now make the tests pass in `tutorial/task11.mu`. The goal is to implement our

colloquial understanding of the “difference” between two numbers.

In lay English, we say the difference between the first-place and third-place

runner in a race is two places. This answer doesn't depend on the order in

which we mention the runners; the difference between third and first is also

two.

The section on [integer arithmetic](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#integer-arithmetic)

is again worth referring to when working on this task.

## Task 12: fun with graphics

Here's a program to draw a rectangle on screen:

```

fn main screen: (addr screen) {

draw-line screen, 0x100/x1 0x100/y1, 0x300/x2 0x100/y2, 3/color=green

draw-line screen, 0x100/x1 0x200/y1, 0x300/x2 0x200/y2, 3/color=green

draw-line screen, 0x100/x1 0x100/y1, 0x100/x2 0x200/y2, 3/color=green

draw-line screen, 0x300/x1 0x100/y1, 0x300/x2 0x200/y2, 3/color=green

}

```

Play around with this function a bit, commenting out some statements with a

leading `#` and rerunning the program. Build up a sense for how the statements

map to lines on screen.

Modify the rectangle to start at the top-left corner on screen. How about

other corners?

Notice the `screen` variable. The `main` function always has access to a

`screen` variable, and any function wanting to draw to the screen will need

this variable. Later you'll learn to create and pass _fake screens_ within

automated tests, so that we can maintain confidence that our graphics

functions work as expected.

The “real” screen on a Mu computer is sized to 1024 (0x400) pixels

wide and 768 (0x300) pixels tall by default. Each pixel can take on [256 colors](http://akkartik.github.io/mu/html/vga_palette.html).

Many other screen configurations are possible, but it'll be up to you to learn

how to get to them.

Graphics in Mu often involve literal integer constants. To help remember what

they mean, you can attach _comment tokens_ -- any string without whitespace --

to a literal integer after a `/`. For example, an argument of `1` can

sometimes mean the width of a line, and at other times mean a boolean with a

true value. Getting into the habit of including comment tokens is an easy way

to make your programs easier to understand.

Another thing to notice in this program is the commas. Commas are entirely

optional in Mu, and it can be handy to drop them selectively to group

arguments together.

This is a good time to skim [Mu's vocabulary of functions for pixel graphics](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/vocabulary.md#pixel-graphics).

They're fun to play with. Once you want to use a specific function, look for

details on the arguments it expects in `signatures.mu`.

## Task 13: reading input from keyboard

Read the section on [events](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/vocabulary.md#events)

from Mu's vocabulary. Write a program to read a key from the keyboard. Mu

receives a keyboard object as the second argument of `main`:

```

fn main screen: (addr screen), keyboard: (addr keyboard) {

# edit in here {

# }

}

```

The _signature_ of `read-key` -- along with many other functions -- is in

[400.mu](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/400.mu).

One wrinkle in this problem is that `read-key` may not actually return a key.

You have to keep retrying until it does. You may have already encountered the

list of `loop` operations in the section on [branches](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#branches).

It might be a good time to refresh your knowledge there.

## Task 14: streams and scanning input from the keyboard

Here's a skeleton of a program for processing text typed in at a keyboard:

```

fn main screen: (addr screen), keyboard: (addr keyboard) {

var in-storage: (stream byte 0x80)

var in/esi: (addr stream byte) <- address in-storage

read-line-from-keyboard keyboard, in, screen, 0xf/fg 0/bg

{

var done?/eax: boolean <- stream-empty? in

compare done?, 0/false

break-if-!=

var g/eax: grapheme <- read-grapheme in

# do stuff with g here

loop

}

}

```

`read-line-from-keyboard` reads keystrokes from the keyboard until you press

the `Enter` (also called `newline`) key, and accumulates them into a _stream_

of bytes. The loop then repeatedly reads _graphemes_ from the stream. A

grapheme can consist of multiple bytes, particularly outside of the Latin

alphabet and Arabic digits most prevalent in the West. Mu doesn't yet support

non-Qwerty keyboards, but support for other keyboards should be easy to add.

This is a good time to skim the section in the Mu reference on

[streams](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#streams), just to

give yourself a sense of what you can do with them. Does the above program

make sense now? Feel free to experiment to make sense of it.

Can you modify it to print out the line a second time, after you've typed it

out until the `Enter` key? Can you print a space after every grapheme when you

print the line out a second time? You'll need to skim the section on

[printing to screen](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/vocabulary.md#printing-to-screen)

from Mu's vocabulary. Pay particular attention to the difference between a

grapheme and a _code-point_. Mu programs often read characters in units of

graphemes, but they must draw in units of code-points that the font manages.

(This adds some complexity but helps combine multiple code-points into a

single glyph as needed for some languages.)

## Task 15: generating cool patterns

Back to drawing to screen. Here's a program that draws every pixel on `screen`

with a `color` equal to the value of its `x` coordinate.

```

fn main screen: (addr screen) {

var y/eax: int <- copy 0

{

compare y, 0x300/screen-height=768

break-if->=

var x/edx: int <- copy 0

{

compare x, 0x400/screen-width=1024

break-if->=

var color/ecx: int <- copy x

color <- and 0xff

pixel screen x, y, color

x <- increment

loop

}

y <- increment

loop

}

}

```

Before you run it, form a hypothesis about what the picture will look like.

The screen is 1024 pixels wide, but there are only 256 colors. What are the

implications of these facts?

After you run this program, try to modify it so every pixel gets a `color`

equal to the sum of its `x` and `y` coordinates. Can you guess what pattern

will result? Play around with more complex formulae. I particularly like the

sum of squares of `x` and `y` coordinates. Check out the [Mandelbrot set](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/apps/mandelbrot-silhouette.mu)

for a really complex example of this sort of _procedural graphics_.

## Task 16: a simple app

We now know how to read keys from keyboard and draw on the screen. Try out

[tutorial/counter.mu](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/tutorial/counter.mu)

which implements a simple counter app.

Open `tutorial/task4.mu` in your text editor. Think about how to add a line

between the `{}` lines to make `the-answer` return 42. Rerun the above

commands. You'll know you got it right when all the tests pass, i.e. when the

rows of dots and text above are replaced by an empty screen.

Don't be afraid to run the above commands over and over again as you try out

different solutions. Here's a way to run them together so they're easy to

repeat.

```

./translate tutorial/task4.mu && qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

In programming there is no penalty for making mistakes, and once you arrive at

the correct solution you have it forever. As always, [feel free to ping me and

ask questions or share your experience](http://akkartik.name/contact).

Mu statements can have _outputs_ on the left (before the `<-`) and _inouts_

(either inputs or outputs) on the right, after the instruction name. The order

matters.

One gotcha to keep in mind is that numbers in Mu must always be in hexadecimal

notation, starting with `0x`. Use a calculator on your computer or phone to

convert 42 to hexadecimal, or [this page on your web browser](http://akkartik.github.io/mu/tutorial/converter.html).

## Task 5: variables in registers, variables in memory

We'll now practice managing one variable in a register (like last time) and

a second one in memory. To prepare for this, reread the first two sections of

the [Mu reference](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md). The

section on [integer arithmetic](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#integer-arithmetic)

also provides a useful cheatsheet of the different forms of instructions you

will need.

Here's the exercise, with comments starting with `#` highlighting the gaps in

the program:

```

fn foo -> _/eax: int {

var x: int

# statement 1: store 3 in x

# statement 2: define a new variable 'y' in register eax and store 4 in it

# statement 3: add y to x, storing the result in x

return x

}

```

Again, you're encouraged to repeatedly try out your programs by running this

command as often as you like:

```

./translate tutorial/task5.mu && qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

The section on [integer arithmetic](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#integer-arithmetic)

shows that Mu consistently follows a few rules:

* Instructions that write to a register always have an output before the `<-`.

* Instructions that use an argument in memory always have it as the first

inout.

* Instructions that write to memory have a preposition in their name. Contrast

`add` to a register vs `add-to` a memory location, `subtract` from a

register vs `subtract-from` a memory location, and so on.

If you're stuck, as always, [my door is open](http://akkartik.name/contact).

You can also see a solution in the repository, though I won't link to it lest

it encourage peeking.

Where possible, try to store variables in registers rather than the stack. The

two main reasons to use the stack are:

* when you need lots of variables and run out of registers, and

* when you have types that don't fit in 32 bits.

## Task 6: getting used to a few error messages

If you're like me, seeing an error message can feel a bit stressful. It

usually happens when you're trying to get somewhere, it can feel like the

computer is being deliberately obtrusive, there's uncertainty about what's

wrong.

Well, I'd like to share one trick I recently learned to stop fearing error

messages: deliberately trigger them at a time and place of your choosing, when

you're mentally prepared to see them. That takes the stress right out.

Here's the skeleton for `tutorial/task6.mu`:

```

fn main {

var m: int

var r/edx: int <- copy 0

# insert a single statement below

}

```

(Reminder: `m` here is stored somewhere in memory, while `r` is stored in

register `edx`. Variables in registers must always be initialized when they're

created. Variables in memory must never be initialized, because they're always

implicitly initialized to 0.)

Now, starting from this skeleton, type the following statements in, one at a

time. Your program should only ever have one more statement than the above

skeleton. We'll try out the following statements, one by one:

* `m <- copy 3`

* `r <- copy 3`

* `copy-to r, 3`

* `copy-to m, 3`

Before typing in each one, write down whether you expect an error. After

trying it out, compare your answer. It can also be useful to write down the

exact error you see, and what it means, in your own words.

(Also, don't forget to delete the statement you typed in before you move on to

trying out the next one.)

Making notes about error messages is an example of a more general trick called

a [runbook](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Runbook). Runbooks are aids to

memory, scripts for what to do when you run into a problem. People think worse

in the presence of stress, and runbooks can help reduce the need for thinking

in the presence of stress. They're a way of programming people (your future

self or others) rather than computers.

## Task 7: variables in registers, variables in memory (again)

Go back to your program in Task 5. Replace the first statement declaring

variable `x`:

```

var x: int

```

so it looks like this:

```

var x/edx: int <- copy 0

```

Run `translate` (or `translate_emulated`) as usual. Use your runbook from Task

6 to address the errors that arise.

## Task 8: primitive statements vs function calls

Managing variables in memory vs register is one of two key skills to

programming in Mu. The second key skill is calling primitives (which are

provided by the x86 instruction set) vs functions (which are defined in terms

of primitives).

To prepare for this task, reread the very first section of the Mu reference,

on [functions and function calls](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#functions).

Now look at the following programs. In each case, write down whether you

expect translation to return any errors and why.

```

fn f a: int {

}

fn main {

f 0

var r/eax: int <- copy 3

f r

var m: int

f m

}

```

(When you're ready, try the above program out as `./translate tutorial/task8a.mu`.)

```

fn f -> _/eax: int {

var result/ecx: int <- copy 0

return result

}

fn main {

var x/eax: int <- f

}

```

(When you're ready, try the above program out as `./translate tutorial/task8b.mu`.)

```

fn f -> _/eax: int {

return 3

}

fn main {

var x/ecx: int <- f

}

```

(When you're ready, try the above program out as `./translate tutorial/task8c.mu`.)

Functions have fewer restrictions than primitives on inouts, but more

restrictions on outputs. Inouts can be registers, or memory, or even literals.

This is why the first example above is legal. Outputs, however, _must_

hard-code specific registers, and function calls must write their outputs to

matching registers. This is why the third example above is illegal.

One subtlety here is that we only require agreement on output registers

between function call and function header. We don't actually have to `return`

the precise register a function header specifies. The return value can even be

a literal integer or in memory somewhere. The `return` is really just a `copy`

to the appropriate register(s). This is why the second example above is legal.

## Task 9: juggling registers between function calls

Here's a program:

```

fn f -> _/eax: int {

return 2

}

fn g -> _/eax: int {

return 3

}

fn add-f-and-g -> _/eax: int {

var x/eax: int <- f

var y/eax: int <- g

x <- add y

return x

}

```

What's wrong with this program? How can you fix it and pass all tests by

modifying just function `add-f-and-g`?

By convention, most functions in Mu return their results in register `eax`.

That creates a fair bit of contention for this register, and we often end up

having to move the output of a function call around to some other location to

free up space for the next function we need to call.

An alternative approach would be to distribute the load between registers so

that different functions use different output registers. That would reduce the

odds of conflict, but not eradicate them entirely. It would also add some

difficulty in calling functions; now you have to remember what register they

write their outputs to. It's unclear if the benefits of this alternative

outweigh the costs, so Mu follows long-established conventions in other

Assembly languages. I do, however, violate the `eax` convention in some cases

where a helper function is only narrowly useful in a single sort of

circumstance and registers are at a premium. See, for example, the definition

of the helper `_read-dithering-error` [when rendering images](http://akkartik.github.io/mu/html/511image.mu.html).

The leading underscore indicates that it's an internal detail of

`render-image`, and not really intended to be called by itself.

## Task 10: operating with fractional numbers

All our variables so far have had type `int` (integer), but there are limits

to what you can do with just whole integers. For example, here's the formula

a visitor to the US will require to convert distances mentioned on road signs

from miles to kilometers:

```

distance * 1.609

```

Write a function to perform this conversion. Some starting points:

* Reread [the section on variables and registers](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#variables-registers-and-memory)

with special attention to the `float` type.

* Read [the section on fractional arithmetic](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#fractional-arithmetic).

* One wrinkle is that the x86 instruction set doesn't permit literal

fractional arguments. So you'll need to _create_ 1.609 somehow. See the

section on moving values around under [operations on simple types](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#operations-on-simple-types).

This task has four source files in the repo that reveal more and more of the

answer. Start from the first, and bump down if you need a hint.

* tutorial/task10.mu

* tutorial/task10-hint1.mu

* tutorial/task10-hint2.mu

* tutorial/task10-hint3.mu

## Task 11: conditionally executing statements

Here's a fragment of Mu code:

```

{

compare x, 0

break-if->=

x <- copy 0

}

```

The combination of `compare` and `break` results in the variable `x` being

assigned 0 _if and only if_ its value was less than 0 at the beginning. The

`break` family of instructions is used to jump to the end of an enclosing `{}`

block if some condition is satisfied, skipping all intervening instructions.

To prepare for this task, read the sections in the Mu reference on

[`compare`](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#comparing-values)

and [branches](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#branches).

Now make the tests pass in `tutorial/task11.mu`. The goal is to implement our

colloquial understanding of the “difference” between two numbers.

In lay English, we say the difference between the first-place and third-place

runner in a race is two places. This answer doesn't depend on the order in

which we mention the runners; the difference between third and first is also

two.

The section on [integer arithmetic](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#integer-arithmetic)

is again worth referring to when working on this task.

## Task 12: fun with graphics

Here's a program to draw a rectangle on screen:

```

fn main screen: (addr screen) {

draw-line screen, 0x100/x1 0x100/y1, 0x300/x2 0x100/y2, 3/color=green

draw-line screen, 0x100/x1 0x200/y1, 0x300/x2 0x200/y2, 3/color=green

draw-line screen, 0x100/x1 0x100/y1, 0x100/x2 0x200/y2, 3/color=green

draw-line screen, 0x300/x1 0x100/y1, 0x300/x2 0x200/y2, 3/color=green

}

```

Play around with this function a bit, commenting out some statements with a

leading `#` and rerunning the program. Build up a sense for how the statements

map to lines on screen.

Modify the rectangle to start at the top-left corner on screen. How about

other corners?

Notice the `screen` variable. The `main` function always has access to a

`screen` variable, and any function wanting to draw to the screen will need

this variable. Later you'll learn to create and pass _fake screens_ within

automated tests, so that we can maintain confidence that our graphics

functions work as expected.

The “real” screen on a Mu computer is sized to 1024 (0x400) pixels

wide and 768 (0x300) pixels tall by default. Each pixel can take on [256 colors](http://akkartik.github.io/mu/html/vga_palette.html).

Many other screen configurations are possible, but it'll be up to you to learn

how to get to them.

Graphics in Mu often involve literal integer constants. To help remember what

they mean, you can attach _comment tokens_ -- any string without whitespace --

to a literal integer after a `/`. For example, an argument of `1` can

sometimes mean the width of a line, and at other times mean a boolean with a

true value. Getting into the habit of including comment tokens is an easy way

to make your programs easier to understand.

Another thing to notice in this program is the commas. Commas are entirely

optional in Mu, and it can be handy to drop them selectively to group

arguments together.

This is a good time to skim [Mu's vocabulary of functions for pixel graphics](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/vocabulary.md#pixel-graphics).

They're fun to play with. Once you want to use a specific function, look for

details on the arguments it expects in `signatures.mu`.

## Task 13: reading input from keyboard

Read the section on [events](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/vocabulary.md#events)

from Mu's vocabulary. Write a program to read a key from the keyboard. Mu

receives a keyboard object as the second argument of `main`:

```

fn main screen: (addr screen), keyboard: (addr keyboard) {

# edit in here {

# }

}

```

The _signature_ of `read-key` -- along with many other functions -- is in

[400.mu](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/400.mu).

One wrinkle in this problem is that `read-key` may not actually return a key.

You have to keep retrying until it does. You may have already encountered the

list of `loop` operations in the section on [branches](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#branches).

It might be a good time to refresh your knowledge there.

## Task 14: streams and scanning input from the keyboard

Here's a skeleton of a program for processing text typed in at a keyboard:

```

fn main screen: (addr screen), keyboard: (addr keyboard) {

var in-storage: (stream byte 0x80)

var in/esi: (addr stream byte) <- address in-storage

read-line-from-keyboard keyboard, in, screen, 0xf/fg 0/bg

{

var done?/eax: boolean <- stream-empty? in

compare done?, 0/false

break-if-!=

var g/eax: grapheme <- read-grapheme in

# do stuff with g here

loop

}

}

```

`read-line-from-keyboard` reads keystrokes from the keyboard until you press

the `Enter` (also called `newline`) key, and accumulates them into a _stream_

of bytes. The loop then repeatedly reads _graphemes_ from the stream. A

grapheme can consist of multiple bytes, particularly outside of the Latin

alphabet and Arabic digits most prevalent in the West. Mu doesn't yet support

non-Qwerty keyboards, but support for other keyboards should be easy to add.

This is a good time to skim the section in the Mu reference on

[streams](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#streams), just to

give yourself a sense of what you can do with them. Does the above program

make sense now? Feel free to experiment to make sense of it.

Can you modify it to print out the line a second time, after you've typed it

out until the `Enter` key? Can you print a space after every grapheme when you

print the line out a second time? You'll need to skim the section on

[printing to screen](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/vocabulary.md#printing-to-screen)

from Mu's vocabulary. Pay particular attention to the difference between a

grapheme and a _code-point_. Mu programs often read characters in units of

graphemes, but they must draw in units of code-points that the font manages.

(This adds some complexity but helps combine multiple code-points into a

single glyph as needed for some languages.)

## Task 15: generating cool patterns

Back to drawing to screen. Here's a program that draws every pixel on `screen`

with a `color` equal to the value of its `x` coordinate.

```

fn main screen: (addr screen) {

var y/eax: int <- copy 0

{

compare y, 0x300/screen-height=768

break-if->=

var x/edx: int <- copy 0

{

compare x, 0x400/screen-width=1024

break-if->=

var color/ecx: int <- copy x

color <- and 0xff

pixel screen x, y, color

x <- increment

loop

}

y <- increment

loop

}

}

```

Before you run it, form a hypothesis about what the picture will look like.

The screen is 1024 pixels wide, but there are only 256 colors. What are the

implications of these facts?

After you run this program, try to modify it so every pixel gets a `color`

equal to the sum of its `x` and `y` coordinates. Can you guess what pattern

will result? Play around with more complex formulae. I particularly like the

sum of squares of `x` and `y` coordinates. Check out the [Mandelbrot set](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/apps/mandelbrot-silhouette.mu)

for a really complex example of this sort of _procedural graphics_.

## Task 16: a simple app

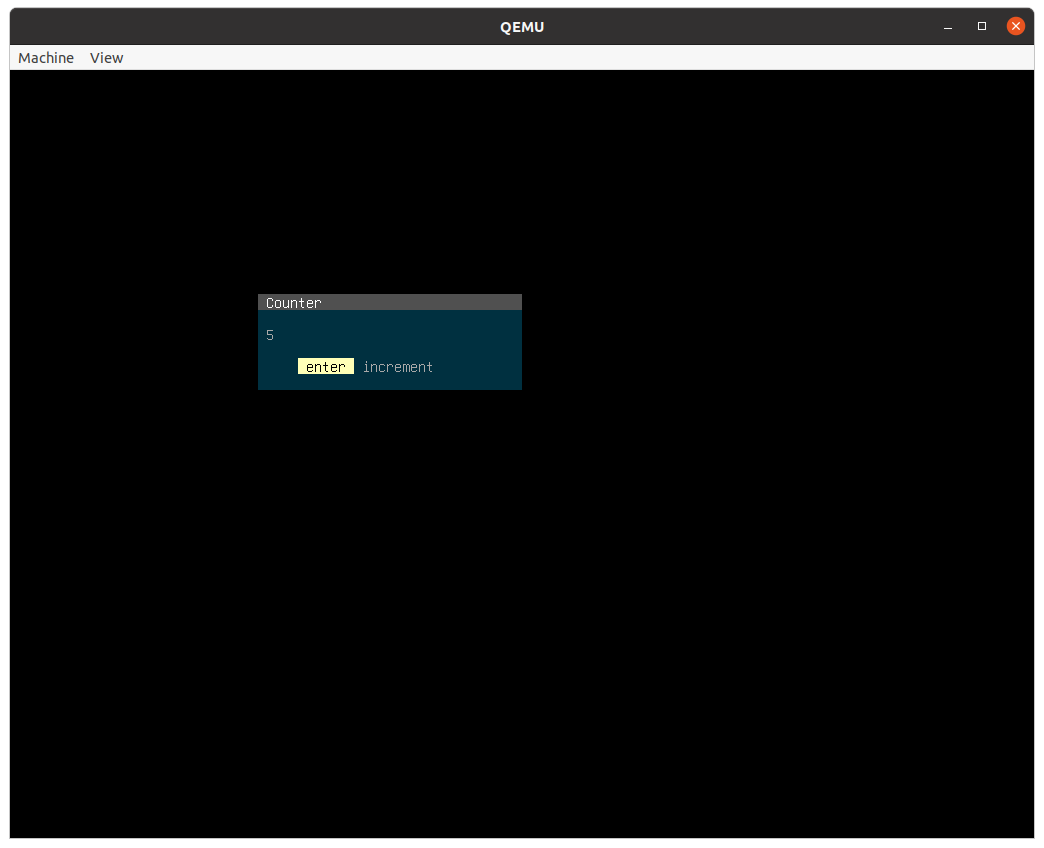

We now know how to read keys from keyboard and draw on the screen. Try out

[tutorial/counter.mu](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/tutorial/counter.mu)

which implements a simple counter app.

Now look at its code. Do all the parts make sense? Reread the extensive

vocabulary of functions for [drawing text to screen](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/vocabulary.md#printing-to-screen).

---

Here's a more challenging problem. Build an app to convert celsius to

fahrenheit and vice versa. Two text fields, the `` key to move the cursor

between them, type in either field and hit `` to populate the other

field.

After you build it, compare your solution with [tutorial/converter.mu](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/tutorial/converter.mu).

A second version breaks the program down into multiple functions, in

[tutorial/converter2.mu](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/tutorial/converter.mu).

Can you see how the two do the same thing? Which one do you like better?

---

There's lots more programs in this repository. Look in the `apps/` directory.

Check out the Mu `shell/`, which persists data between runs to a separate data

disk. Hopefully this gives you some sense for how little software it takes to

build useful programs for yourself. Do you have any new ideas for programs to

write in Mu? [Tell me about them!](http://akkartik.name/about) I'd love to jam

with you.

Now look at its code. Do all the parts make sense? Reread the extensive

vocabulary of functions for [drawing text to screen](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/vocabulary.md#printing-to-screen).

---

Here's a more challenging problem. Build an app to convert celsius to

fahrenheit and vice versa. Two text fields, the `` key to move the cursor

between them, type in either field and hit `` to populate the other

field.

After you build it, compare your solution with [tutorial/converter.mu](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/tutorial/converter.mu).

A second version breaks the program down into multiple functions, in

[tutorial/converter2.mu](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/tutorial/converter.mu).

Can you see how the two do the same thing? Which one do you like better?

---

There's lots more programs in this repository. Look in the `apps/` directory.

Check out the Mu `shell/`, which persists data between runs to a separate data

disk. Hopefully this gives you some sense for how little software it takes to

build useful programs for yourself. Do you have any new ideas for programs to

write in Mu? [Tell me about them!](http://akkartik.name/about) I'd love to jam

with you.

If you have any trouble at this point, don't waste _any_ time thinking about

it. Just [get in touch](http://akkartik.name/contact).

(You can look at `tutorial/task1.mu` at this point if you like. It's just 3

lines long. But don't worry if it doesn't make much sense.)

## Task 2: running automated tests

Here's a new program to run:

```

./translate tutorial/task2.mu

qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

(As before, I'll leave you to substitute `translate` with `translate_emulated`

if you're not on Linux.)

This time the screen will look like this:

If you have any trouble at this point, don't waste _any_ time thinking about

it. Just [get in touch](http://akkartik.name/contact).

(You can look at `tutorial/task1.mu` at this point if you like. It's just 3

lines long. But don't worry if it doesn't make much sense.)

## Task 2: running automated tests

Here's a new program to run:

```

./translate tutorial/task2.mu

qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

(As before, I'll leave you to substitute `translate` with `translate_emulated`

if you're not on Linux.)

This time the screen will look like this:

Each of the dots represents an automated _test_, a little self-contained and

automated program run and its results verified. Mu comes with a lot of tests

(every function starting with 'test-' is a test), and it always runs all tests

on boot before it runs any program. You may have missed the dots when you ran

Task 1 because there were no failures. They were printed on the screen and

then immediately erased. In Task 2, however, we've deliberately included a

failing test. When any tests fail, Mu will immediately stop, showing you

messages from failing tests and implicitly asking you to first fix them. A lot

of learning programming is about building a sense for when you need to write

tests for the code you write.

(Don't worry just yet about what the message in the middle of all the dots means.)

## Task 3: configure your text editor

So far we haven't used a text editor yet, but we will now be starting to do

so. Before we do, it's worth spending a little bit of time setting your

preferred editor up to be a little more ergonomic. Mu comes with _syntax

highlighting_ settings for a few common text editors in the `editor/`

sub-directory. If you don't see your text editor there, or if you don't know

what to do with those files, [get in touch!](http://akkartik.name/contact)

Here's what my editor (Vim) looks like with these settings on the program of

Task 1:

Each of the dots represents an automated _test_, a little self-contained and

automated program run and its results verified. Mu comes with a lot of tests

(every function starting with 'test-' is a test), and it always runs all tests

on boot before it runs any program. You may have missed the dots when you ran

Task 1 because there were no failures. They were printed on the screen and

then immediately erased. In Task 2, however, we've deliberately included a

failing test. When any tests fail, Mu will immediately stop, showing you

messages from failing tests and implicitly asking you to first fix them. A lot

of learning programming is about building a sense for when you need to write

tests for the code you write.

(Don't worry just yet about what the message in the middle of all the dots means.)

## Task 3: configure your text editor

So far we haven't used a text editor yet, but we will now be starting to do

so. Before we do, it's worth spending a little bit of time setting your

preferred editor up to be a little more ergonomic. Mu comes with _syntax

highlighting_ settings for a few common text editors in the `editor/`

sub-directory. If you don't see your text editor there, or if you don't know

what to do with those files, [get in touch!](http://akkartik.name/contact)

Here's what my editor (Vim) looks like with these settings on the program of

Task 1:

It's particularly useful to highlight _comments_ which the computer ignores

(everything on a line after a `#` character) and _strings_ within `""` double

quotes.

## Task 4: your first Mu statement

Mu is a statement-oriented language. Most statements translate into a single

instruction to the x86 processor. Quickly read the first two sections of the

[Mu reference](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md) (about

functions and variables) to learn a little bit about it. It's ok if it doesn't

all make sense just yet. We'll reread it later.

Here's a skeleton of a Mu function that's missing a single statement.

```

fn the-answer -> _/eax: int {

var result/eax: int <- copy 0

# insert your statement below {

# }

return result

}

```

Try running it now:

```

./translate tutorial/task4.mu

qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

(As before, I'll leave you to substitute `translate` with `translate_emulated`

if you're not on Linux.)

You should see a failing test that looks something like this:

It's particularly useful to highlight _comments_ which the computer ignores

(everything on a line after a `#` character) and _strings_ within `""` double

quotes.

## Task 4: your first Mu statement

Mu is a statement-oriented language. Most statements translate into a single

instruction to the x86 processor. Quickly read the first two sections of the

[Mu reference](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md) (about

functions and variables) to learn a little bit about it. It's ok if it doesn't

all make sense just yet. We'll reread it later.

Here's a skeleton of a Mu function that's missing a single statement.

```

fn the-answer -> _/eax: int {

var result/eax: int <- copy 0

# insert your statement below {

# }

return result

}

```

Try running it now:

```

./translate tutorial/task4.mu

qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

(As before, I'll leave you to substitute `translate` with `translate_emulated`

if you're not on Linux.)

You should see a failing test that looks something like this:

Open `tutorial/task4.mu` in your text editor. Think about how to add a line

between the `{}` lines to make `the-answer` return 42. Rerun the above

commands. You'll know you got it right when all the tests pass, i.e. when the

rows of dots and text above are replaced by an empty screen.

Don't be afraid to run the above commands over and over again as you try out

different solutions. Here's a way to run them together so they're easy to

repeat.

```

./translate tutorial/task4.mu && qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

In programming there is no penalty for making mistakes, and once you arrive at

the correct solution you have it forever. As always, [feel free to ping me and

ask questions or share your experience](http://akkartik.name/contact).

Mu statements can have _outputs_ on the left (before the `<-`) and _inouts_

(either inputs or outputs) on the right, after the instruction name. The order

matters.

One gotcha to keep in mind is that numbers in Mu must always be in hexadecimal

notation, starting with `0x`. Use a calculator on your computer or phone to

convert 42 to hexadecimal, or [this page on your web browser](http://akkartik.github.io/mu/tutorial/converter.html).

## Task 5: variables in registers, variables in memory

We'll now practice managing one variable in a register (like last time) and

a second one in memory. To prepare for this, reread the first two sections of

the [Mu reference](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md). The

section on [integer arithmetic](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#integer-arithmetic)

also provides a useful cheatsheet of the different forms of instructions you

will need.

Here's the exercise, with comments starting with `#` highlighting the gaps in

the program:

```

fn foo -> _/eax: int {

var x: int

# statement 1: store 3 in x

# statement 2: define a new variable 'y' in register eax and store 4 in it

# statement 3: add y to x, storing the result in x

return x

}

```

Again, you're encouraged to repeatedly try out your programs by running this

command as often as you like:

```

./translate tutorial/task5.mu && qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

The section on [integer arithmetic](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#integer-arithmetic)

shows that Mu consistently follows a few rules:

* Instructions that write to a register always have an output before the `<-`.

* Instructions that use an argument in memory always have it as the first

inout.

* Instructions that write to memory have a preposition in their name. Contrast

`add` to a register vs `add-to` a memory location, `subtract` from a

register vs `subtract-from` a memory location, and so on.

If you're stuck, as always, [my door is open](http://akkartik.name/contact).

You can also see a solution in the repository, though I won't link to it lest

it encourage peeking.

Where possible, try to store variables in registers rather than the stack. The

two main reasons to use the stack are:

* when you need lots of variables and run out of registers, and

* when you have types that don't fit in 32 bits.

## Task 6: getting used to a few error messages

If you're like me, seeing an error message can feel a bit stressful. It

usually happens when you're trying to get somewhere, it can feel like the

computer is being deliberately obtrusive, there's uncertainty about what's

wrong.

Well, I'd like to share one trick I recently learned to stop fearing error

messages: deliberately trigger them at a time and place of your choosing, when

you're mentally prepared to see them. That takes the stress right out.

Here's the skeleton for `tutorial/task6.mu`:

```

fn main {

var m: int

var r/edx: int <- copy 0

# insert a single statement below

}

```

(Reminder: `m` here is stored somewhere in memory, while `r` is stored in

register `edx`. Variables in registers must always be initialized when they're

created. Variables in memory must never be initialized, because they're always

implicitly initialized to 0.)

Now, starting from this skeleton, type the following statements in, one at a

time. Your program should only ever have one more statement than the above

skeleton. We'll try out the following statements, one by one:

* `m <- copy 3`

* `r <- copy 3`

* `copy-to r, 3`

* `copy-to m, 3`

Before typing in each one, write down whether you expect an error. After

trying it out, compare your answer. It can also be useful to write down the

exact error you see, and what it means, in your own words.

(Also, don't forget to delete the statement you typed in before you move on to

trying out the next one.)

Making notes about error messages is an example of a more general trick called

a [runbook](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Runbook). Runbooks are aids to

memory, scripts for what to do when you run into a problem. People think worse

in the presence of stress, and runbooks can help reduce the need for thinking

in the presence of stress. They're a way of programming people (your future

self or others) rather than computers.

## Task 7: variables in registers, variables in memory (again)

Go back to your program in Task 5. Replace the first statement declaring

variable `x`:

```

var x: int

```

so it looks like this:

```

var x/edx: int <- copy 0

```

Run `translate` (or `translate_emulated`) as usual. Use your runbook from Task

6 to address the errors that arise.

## Task 8: primitive statements vs function calls

Managing variables in memory vs register is one of two key skills to

programming in Mu. The second key skill is calling primitives (which are

provided by the x86 instruction set) vs functions (which are defined in terms

of primitives).

To prepare for this task, reread the very first section of the Mu reference,

on [functions and function calls](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#functions).

Now look at the following programs. In each case, write down whether you

expect translation to return any errors and why.

```

fn f a: int {

}

fn main {

f 0

var r/eax: int <- copy 3

f r

var m: int

f m

}

```

(When you're ready, try the above program out as `./translate tutorial/task8a.mu`.)

```

fn f -> _/eax: int {

var result/ecx: int <- copy 0

return result

}

fn main {

var x/eax: int <- f

}

```

(When you're ready, try the above program out as `./translate tutorial/task8b.mu`.)

```

fn f -> _/eax: int {

return 3

}

fn main {

var x/ecx: int <- f

}

```

(When you're ready, try the above program out as `./translate tutorial/task8c.mu`.)

Functions have fewer restrictions than primitives on inouts, but more

restrictions on outputs. Inouts can be registers, or memory, or even literals.

This is why the first example above is legal. Outputs, however, _must_

hard-code specific registers, and function calls must write their outputs to

matching registers. This is why the third example above is illegal.

One subtlety here is that we only require agreement on output registers

between function call and function header. We don't actually have to `return`

the precise register a function header specifies. The return value can even be

a literal integer or in memory somewhere. The `return` is really just a `copy`

to the appropriate register(s). This is why the second example above is legal.

## Task 9: juggling registers between function calls

Here's a program:

```

fn f -> _/eax: int {

return 2

}

fn g -> _/eax: int {

return 3

}

fn add-f-and-g -> _/eax: int {

var x/eax: int <- f

var y/eax: int <- g

x <- add y

return x

}

```

What's wrong with this program? How can you fix it and pass all tests by

modifying just function `add-f-and-g`?

By convention, most functions in Mu return their results in register `eax`.

That creates a fair bit of contention for this register, and we often end up

having to move the output of a function call around to some other location to

free up space for the next function we need to call.

An alternative approach would be to distribute the load between registers so

that different functions use different output registers. That would reduce the

odds of conflict, but not eradicate them entirely. It would also add some

difficulty in calling functions; now you have to remember what register they

write their outputs to. It's unclear if the benefits of this alternative

outweigh the costs, so Mu follows long-established conventions in other

Assembly languages. I do, however, violate the `eax` convention in some cases

where a helper function is only narrowly useful in a single sort of

circumstance and registers are at a premium. See, for example, the definition

of the helper `_read-dithering-error` [when rendering images](http://akkartik.github.io/mu/html/511image.mu.html).

The leading underscore indicates that it's an internal detail of

`render-image`, and not really intended to be called by itself.

## Task 10: operating with fractional numbers

All our variables so far have had type `int` (integer), but there are limits

to what you can do with just whole integers. For example, here's the formula

a visitor to the US will require to convert distances mentioned on road signs

from miles to kilometers:

```

distance * 1.609

```

Write a function to perform this conversion. Some starting points:

* Reread [the section on variables and registers](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#variables-registers-and-memory)

with special attention to the `float` type.

* Read [the section on fractional arithmetic](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#fractional-arithmetic).

* One wrinkle is that the x86 instruction set doesn't permit literal

fractional arguments. So you'll need to _create_ 1.609 somehow. See the

section on moving values around under [operations on simple types](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#operations-on-simple-types).

This task has four source files in the repo that reveal more and more of the

answer. Start from the first, and bump down if you need a hint.

* tutorial/task10.mu

* tutorial/task10-hint1.mu

* tutorial/task10-hint2.mu

* tutorial/task10-hint3.mu

## Task 11: conditionally executing statements

Here's a fragment of Mu code:

```

{

compare x, 0

break-if->=

x <- copy 0

}

```

The combination of `compare` and `break` results in the variable `x` being

assigned 0 _if and only if_ its value was less than 0 at the beginning. The

`break` family of instructions is used to jump to the end of an enclosing `{}`

block if some condition is satisfied, skipping all intervening instructions.

To prepare for this task, read the sections in the Mu reference on

[`compare`](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#comparing-values)

and [branches](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#branches).

Now make the tests pass in `tutorial/task11.mu`. The goal is to implement our

colloquial understanding of the “difference” between two numbers.

In lay English, we say the difference between the first-place and third-place

runner in a race is two places. This answer doesn't depend on the order in

which we mention the runners; the difference between third and first is also

two.

The section on [integer arithmetic](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#integer-arithmetic)

is again worth referring to when working on this task.

## Task 12: fun with graphics

Here's a program to draw a rectangle on screen:

```

fn main screen: (addr screen) {

draw-line screen, 0x100/x1 0x100/y1, 0x300/x2 0x100/y2, 3/color=green

draw-line screen, 0x100/x1 0x200/y1, 0x300/x2 0x200/y2, 3/color=green

draw-line screen, 0x100/x1 0x100/y1, 0x100/x2 0x200/y2, 3/color=green

draw-line screen, 0x300/x1 0x100/y1, 0x300/x2 0x200/y2, 3/color=green

}

```

Play around with this function a bit, commenting out some statements with a

leading `#` and rerunning the program. Build up a sense for how the statements

map to lines on screen.

Modify the rectangle to start at the top-left corner on screen. How about

other corners?

Notice the `screen` variable. The `main` function always has access to a

`screen` variable, and any function wanting to draw to the screen will need

this variable. Later you'll learn to create and pass _fake screens_ within

automated tests, so that we can maintain confidence that our graphics

functions work as expected.

The “real” screen on a Mu computer is sized to 1024 (0x400) pixels

wide and 768 (0x300) pixels tall by default. Each pixel can take on [256 colors](http://akkartik.github.io/mu/html/vga_palette.html).

Many other screen configurations are possible, but it'll be up to you to learn

how to get to them.

Graphics in Mu often involve literal integer constants. To help remember what

they mean, you can attach _comment tokens_ -- any string without whitespace --

to a literal integer after a `/`. For example, an argument of `1` can

sometimes mean the width of a line, and at other times mean a boolean with a

true value. Getting into the habit of including comment tokens is an easy way

to make your programs easier to understand.

Another thing to notice in this program is the commas. Commas are entirely

optional in Mu, and it can be handy to drop them selectively to group

arguments together.

This is a good time to skim [Mu's vocabulary of functions for pixel graphics](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/vocabulary.md#pixel-graphics).

They're fun to play with. Once you want to use a specific function, look for

details on the arguments it expects in `signatures.mu`.

## Task 13: reading input from keyboard

Read the section on [events](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/vocabulary.md#events)

from Mu's vocabulary. Write a program to read a key from the keyboard. Mu

receives a keyboard object as the second argument of `main`:

```

fn main screen: (addr screen), keyboard: (addr keyboard) {

# edit in here {

# }

}

```

The _signature_ of `read-key` -- along with many other functions -- is in

[400.mu](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/400.mu).

One wrinkle in this problem is that `read-key` may not actually return a key.

You have to keep retrying until it does. You may have already encountered the

list of `loop` operations in the section on [branches](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#branches).

It might be a good time to refresh your knowledge there.

## Task 14: streams and scanning input from the keyboard

Here's a skeleton of a program for processing text typed in at a keyboard:

```

fn main screen: (addr screen), keyboard: (addr keyboard) {

var in-storage: (stream byte 0x80)

var in/esi: (addr stream byte) <- address in-storage

read-line-from-keyboard keyboard, in, screen, 0xf/fg 0/bg

{

var done?/eax: boolean <- stream-empty? in

compare done?, 0/false

break-if-!=

var g/eax: grapheme <- read-grapheme in

# do stuff with g here

loop

}

}

```

`read-line-from-keyboard` reads keystrokes from the keyboard until you press

the `Enter` (also called `newline`) key, and accumulates them into a _stream_

of bytes. The loop then repeatedly reads _graphemes_ from the stream. A

grapheme can consist of multiple bytes, particularly outside of the Latin

alphabet and Arabic digits most prevalent in the West. Mu doesn't yet support

non-Qwerty keyboards, but support for other keyboards should be easy to add.

This is a good time to skim the section in the Mu reference on

[streams](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#streams), just to

give yourself a sense of what you can do with them. Does the above program

make sense now? Feel free to experiment to make sense of it.

Can you modify it to print out the line a second time, after you've typed it

out until the `Enter` key? Can you print a space after every grapheme when you

print the line out a second time? You'll need to skim the section on

[printing to screen](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/vocabulary.md#printing-to-screen)

from Mu's vocabulary. Pay particular attention to the difference between a

grapheme and a _code-point_. Mu programs often read characters in units of

graphemes, but they must draw in units of code-points that the font manages.

(This adds some complexity but helps combine multiple code-points into a

single glyph as needed for some languages.)

## Task 15: generating cool patterns

Back to drawing to screen. Here's a program that draws every pixel on `screen`

with a `color` equal to the value of its `x` coordinate.

```

fn main screen: (addr screen) {

var y/eax: int <- copy 0

{

compare y, 0x300/screen-height=768

break-if->=

var x/edx: int <- copy 0

{

compare x, 0x400/screen-width=1024

break-if->=

var color/ecx: int <- copy x

color <- and 0xff

pixel screen x, y, color

x <- increment

loop

}

y <- increment

loop

}

}

```

Before you run it, form a hypothesis about what the picture will look like.

The screen is 1024 pixels wide, but there are only 256 colors. What are the

implications of these facts?

After you run this program, try to modify it so every pixel gets a `color`

equal to the sum of its `x` and `y` coordinates. Can you guess what pattern

will result? Play around with more complex formulae. I particularly like the

sum of squares of `x` and `y` coordinates. Check out the [Mandelbrot set](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/apps/mandelbrot-silhouette.mu)

for a really complex example of this sort of _procedural graphics_.

## Task 16: a simple app

We now know how to read keys from keyboard and draw on the screen. Try out

[tutorial/counter.mu](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/tutorial/counter.mu)

which implements a simple counter app.

Open `tutorial/task4.mu` in your text editor. Think about how to add a line

between the `{}` lines to make `the-answer` return 42. Rerun the above

commands. You'll know you got it right when all the tests pass, i.e. when the

rows of dots and text above are replaced by an empty screen.

Don't be afraid to run the above commands over and over again as you try out

different solutions. Here's a way to run them together so they're easy to

repeat.

```

./translate tutorial/task4.mu && qemu-system-i386 code.img

```

In programming there is no penalty for making mistakes, and once you arrive at

the correct solution you have it forever. As always, [feel free to ping me and

ask questions or share your experience](http://akkartik.name/contact).

Mu statements can have _outputs_ on the left (before the `<-`) and _inouts_

(either inputs or outputs) on the right, after the instruction name. The order

matters.

One gotcha to keep in mind is that numbers in Mu must always be in hexadecimal

notation, starting with `0x`. Use a calculator on your computer or phone to

convert 42 to hexadecimal, or [this page on your web browser](http://akkartik.github.io/mu/tutorial/converter.html).

## Task 5: variables in registers, variables in memory

We'll now practice managing one variable in a register (like last time) and

a second one in memory. To prepare for this, reread the first two sections of

the [Mu reference](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md). The

section on [integer arithmetic](https://github.com/akkartik/mu/blob/main/mu.md#integer-arithmetic)

also provides a useful cheatsheet of the different forms of instructions you

will need.

Here's the exercise, with comments starting with `#` highlighting the gaps in

the program:

```

fn foo -> _/eax: int {

var x: int

# statement 1: store 3 in x

# statement 2: define a new variable 'y' in register eax and store 4 in it

# statement 3: add y to x, storing the result in x

return x

}

```

Again, you're encouraged to repeatedly try out your programs by running this

command as often as you like:

```