|

|

Until now, you may have felt that the programs you've been writing in Scheme don't act like other computer programs you've used. In this chapter and the next, we're going to tie together almost everything you've learned so far to write a spreadsheet program, just like the ones accountants use.

This chapter describes the operation of the spreadsheet program, as a user manual would. The next chapter explains how the program is implemented in Scheme.

You can load our program into Scheme by typing

(load "spread.scm")

To start the program, invoke the procedure spreadsheet with no

arguments; to quit the spreadsheet program, type exit.

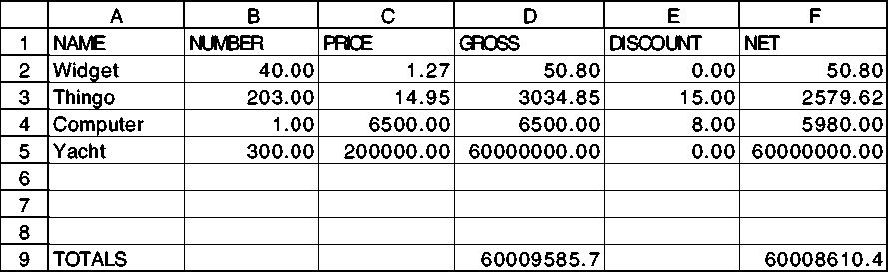

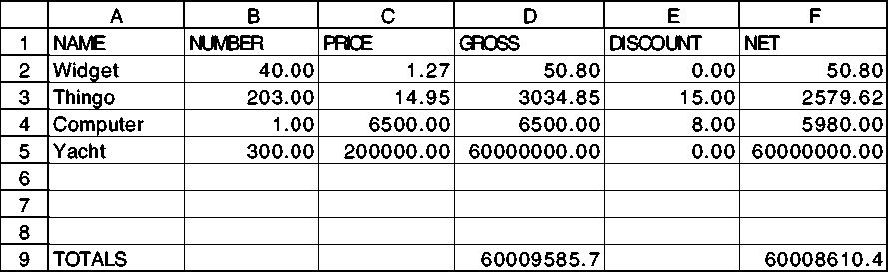

A spreadsheet is a program that displays information in two dimensions on

the screen. It can also compute some of the information automatically. Below

is an example of a display from our spreadsheet program. The

display is a rectangle of information with six columns and 20 rows. The

intersection of a row with a column is called a cell; for

example, the cell c4 contains the number 6500. The column letters

(a through f) and row numbers are provided by the spreadsheet

program, as is the information on the bottom few lines, which we'll talk

about later. (The ?? at the very bottom is the spreadsheet prompt;

you type commands on that line.) We typed most of the entries in the cells,

using commands such as

(put 6500 c4)

-----a---- -----b---- -----c---- -----d---- -----e---- -----f---- 1 NAME NUMBER PRICE GROSS DISCOUNT NET 2 Widget 40.00 1.27 50.80 0.00 50.80 3 Thingo 203.00 14.95 > 3034.85< 15.00 2579.62 4 Computer 1.00 6500.00 6500.00 8.00 5980.00 5 Yacht 300.00 200000.00 60000000.+ 0.00 60000000.+ 6 7 8 9 TOTALS 60009585.+ 60008610.+ 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 d3: 3034.85 (* b3 c3) ??

What's most useful about a spreadsheet is its ability to compute some of the

cell values itself. For example, every number in column d is the

product of the numbers in columns b and c of the same row.

Instead of putting a particular number in a particular cell, we put a formula in all the cells of the column at once.[1] This implies that when we change the value of one cell, other

cells will be updated automatically. For example, if we put the number 5

into cell b4, the spreadsheet will look like this:

-----a---- -----b---- -----c---- -----d---- -----e---- -----f---- 1 NAME NUMBER PRICE GROSS DISCOUNT NET 2 Widget 40.00 1.27 50.80 0.00 50.80 3 Thingo 203.00 14.95 > 3034.85< 15.00 2579.62 4 Computer 5.00 6500.00 32500.00 8.00 29900.00 5 Yacht 300.00 200000.00 60000000.+ 0.00 60000000.+ 6 7 8 9 TOTALS 60035585.+ 60032530.+ 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 d3: 3034.85 (* b3 c3) ??

In addition to cell b4, the spreadsheet program has changed

the values in d4, f4, d9, and f9.

One detail we haven't mentioned so far is that at any moment there is one

selected cell. Right now cell d3 is selected. You can tell

that because of the arrowheads surrounding it in the display, like this:

> 3034.85<

Also, the lines

d3: 3034.85 (* b3 c3)

at the bottom of the screen mean that cell d3 is selected,

its value is 3034.85, and its formula is (* b3 c3).

In commercial spreadsheet programs, you generally select a cell with arrow keys or by clicking on it with a mouse. The highlighted cell is typically displayed in inverse video, and there might be thin lines drawn in a grid on the screen to separate the cells.

Our program leaves all this out for two reasons. First, details like this don't add very much to what you learn from studying the program, but they take a disproportionate effort to get exactly right. Second, the facilities needed in Scheme to control screen graphics are specific to each model of computer. We couldn't write a single program that would work in all versions of Scheme. (A program that works in all versions is called portable.)

Similarly, our program prints an entire new screenful of information after every command. A better program would change only the parts of the screen for which the corresponding values have changed. But there is no uniform way to ask Scheme to print at a particular position on the screen; some versions of Scheme can do that, but not using standard procedures.

Also, of course, if you spend $500 on a spreadsheet program, it will have hundreds of bells and whistles, such as graphing, printing your spreadsheet on paper, changing the widths of columns, and undoing the last command you typed. But each of those is a straightforward extension. We didn't write them all because there are only two of us and we're not getting paid enough! You'll add some features as exercises.

When you begin the spreadsheet program, you will see an empty grid and a prompt at the bottom of the screen.

Most spreadsheet programs are controlled using single-keystroke commands (or

equivalent mouse clicks). That's another thing we can't do entirely

portably in Scheme. We've tried to compromise by including one-letter

command names in our program, but you do have to type the return or

enter key after each command. The single-letter commands are for

simple operations, such as selecting a cell one position up, down, left, or

right from the previously selected cell.

For more complicated commands, such as entering values, a longer notation is obviously required. In our program we use a notation that looks very much like that of a Scheme program: A command consists of a name and some arguments, all enclosed in parentheses. However, the spreadsheet commands are not Scheme expressions. In particular, the arguments are not evaluated as they would be in Scheme. For example, earlier we said

(put 6500 c4)

If this were a Scheme expression, we would have had to quote the second argument:

(put 6500 'c4) ;; wrong!

There are four one-letter commands to move to a new selected cell:

| Command Name | Meaning |

|---|---|

f | move Forward (right) |

b | move Back (left) |

n | move to Next line (down) |

p | move to Previous line (up) |

If you want to move one step, you can just type the letter f, b,

n, or p on a line by itself. If you want to move farther, you

can invoke the same commands in Scheme notation, with the distance to move

as an argument:

?? (f 4)

Another way to move the selection is to choose a particular cell by name.

The command for this is called select:

(select e12)

The spreadsheet grid includes columns a through z and rows 1 through 30. Not all of it can fit on the screen at once. If you

select a cell that's not shown on the screen, then the program will shift

the entire screen display so that the rows and columns shown will include

the newly selected cell.

As we've already seen, the put command is used to put a value in a

particular cell. It can be used with either one or two arguments. The

first (or only) argument is a value. If there is a second argument, it is

the (unquoted) name of the desired cell. If not, the currently selected

cell will be used.

A value can be a number or a quoted word. (As in Scheme programming, most

words can be quoted using the single-quote notation 'word, but words

that include spaces, mixed-case letters, or some punctuation characters must

be quoted using the double-quote string notation "Widget".)

However, non-numeric words are used only as labels; they can't provide

values for formulas that compute values in other cells.

The program displays numbers differently from labels. If the value in a cell is a number, it is displayed at the right edge of its cell, and it is shown with two digits following the decimal point. (Look again at the screen samples earlier in this chapter.) If the value is a non-numeric word, it is displayed at the left edge of its cell.

If the value is too wide to fit in the cell (that is, more than ten

characters wide), then the program prints the first nine characters followed

by a plus sign (+) to indicate that there is more information than is

visible. (If you want to see the full value in such a cell, select it and

look at the bottom of the screen.)

To erase the value from a cell, you can put an empty list () in it.

With this one exception, lists are not allowed as cell values.

It's possible to put a value in an entire row or column, instead of just one

cell. To do this, use the row number or the column letter as the second

argument to put. Here's an example:

(put 'peter d)

This command will put the word peter into all the cells in

column d. (Remember that not all the cells are visible at once, but

even the invisible ones are affected. Cells d1 through d30 are

given values by this command.)

What happens if you ask to fill an entire row or column at once, but some of the cells already have values? In this case, only the vacant cells will be affected. The only exception is that if the value you are using is the empty list, indicating that you want to erase old values, then the entire row or column is affected. (So if you put a formula in an entire row or column and then change your mind, you must erase the old one before you can install a new one.)

We mentioned earlier that the value of one cell can be made to depend on the

values of other cells. This, too, is done using the put command. The

difference is that instead of putting a constant value into a cell, you can

put a formula in the cell. Here's an example:

(put (+ b3 c5) d6)

This command says that the value in cell d6 should be the

sum of the values in b3 and c5. The command may or may not have

any immediately visible effect; it depends on whether those two cells

already have values. If so, a value will immediately appear in d6;

if not, nothing happens until you put values into b3 and c5.

If you erase the value in a cell, then any cells that depend on it are

also erased. For example, if you erase the value in b3, then the

value in d6 will disappear also.

So far we've seen only one example of a formula; it asks for the sum of two cells. Formulas, like Scheme expressions, can include invocations of functions with sub-formulas as the arguments.

(put (* d6 (+ b4 92)) a3)

The "atomic" formulas are constants (numbers or quoted words)

and cell references (such as b4 in our example).

Not every Scheme function can be used in a formula. Most important, there

is no lambda in the spreadsheet language, so you can't invent your own

functions. Also, since formulas can be based only on numbers, only the

numeric functions can be used.

Although we've presented the idea of putting a formula in a cell separately from the idea of putting a value in a cell, a value is really just a particularly simple formula. The program makes no distinction internally between these two cases. (Since a constant formula doesn't depend on any other cells, its value is always displayed right away.)

We mentioned that a value can be put into an entire row or column at

once. The same is true of formulas in general. But this capability gives

rise to a slight complication. The typical situation is that each cell in

the row or column should be computed using the same algorithm, but based on

different values. For example, in the spreadsheet at the beginning of the

chapter, every cell in column d is the product of a cell in column

b and a cell in column c, but not the same cell for

every row. If we used a formula like

(put (* b2 c2) d)

then every cell in column d would have the value 50.80.

Instead we want the equivalent of

(put (* b2 c2) d2) (put (* b3 c3) d3) (put (* b4 c4) d4)

and so on. The spreadsheet program meets this need by providing a notation for cells that indicates position relative to the cell being computed, rather than by name. In our case we could say

(put (* (cell b) (cell c)) d)

Cell can take one or two arguments. In this example we've used the

one-argument version. The argument must be either a letter, to indicate a

column, or a number between 1 and 30, to indicate a row. Whichever

dimension (row or column) is not specified by the argument will be

the same as that of the cell being computed. So, for example, if we are

computing a value for cell d5, then (cell b) refers to cell b5, but (cell 12) would refer to cell d12.

The one-argument form of cell is adequate for many situations, but not

if you want a cell to depend on one that's both in a different row and in a

different column. For example, suppose you wanted to compute the change

of a number across various columns, like this:

-----a---- -----b---- -----c---- -----d---- -----e---- -----f---- 1 MONTH January February March April May 2 PRICE 70.00 74.00 79.00 76.50 81.00 3 CHANGE 4.00 5.00 -2.50 4.50

The value of cell d3, for example, is a function of the

values of cells d2 and c2.

To create this spreadsheet, we said

(put (- (cell 2) (cell <1 2)) 3)

The first appearance of cell asks for the value of the cell

immediately above the one being calculated. (That is, it asks for the cell

in row 2 of the same column.) But the one-argument notation doesn't allow

us to ask for the cell above and to the left.

In the two-argument version, the first argument determines the column and

the second determines the row. Each argument can take any of several

forms. It can be a letter (for the column) or number (for the row), to

indicate a specific column or row. It can be an asterisk (*) to

indicate the same column or row as the cell being calculated. Finally,

either argument can take the form <3 to indicate a cell three before

the one being calculated (above or to the left, depending on whether this is

the row or column argument) or >5 to indicate a cell five after this

one (below or to the right).

So any of the following formulas would have let us calculate the change in this example:

(put (- (cell 2) (cell <1 2)) 3) (put (- (cell 2) (cell <1 <1)) 3) (put (- (cell * 2) (cell <1 2)) 3) (put (- (cell * <1) (cell <1 2)) 3) (put (- (cell <0 <1) (cell <1 <1)) 3)

When a formula is put into every cell in a particular row or column, it may

not be immediately computable for all those cells. The value for each cell

will depend on the values of the cells to which the formula refers, and some

of those cells may not have values. (If a cell has a non-numeric value,

that's the same as not having a value at all for this purpose.) New values

are computed only for those cells for which the formula is computable. For

example, cell b3 in the monthly change display has the formula (- b2 a2), but the value of cell a2 is the label PRICE, so no

value is computed for b3.

Formulas can be used in two ways. We've seen that a formula can be associated with a cell, so that changes to one cell can automatically recompute the value of another. You can also type a formula directly to the spreadsheet prompt, in which case the value of the formula will be shown at the bottom of the screen. In a formula used in this way, cell references relative to "the cell being computed" refer instead to the selected cell.

Sometimes you use a series of several spreadsheet commands to set up some computation. For example, we had to use several commands such as

(put "Thingo" a3)

to set up the sample spreadsheet displays at the beginning of this chapter.

If you want to avoid retyping such a series of commands, you can put the commands in a file using a text editor. Then, in the spreadsheet program, use the command

(load "filename")

This looks just like Scheme's load (on purpose), but it's

not the same thing; the file that it loads must contain spreadsheet

commands, not Scheme expressions. It will list the commands from the file

as it carries them out.

We've talked throughout this book about the importance of abstraction,

the act of giving a name to some process or structure. Writing an

application program can be seen as the ultimate in abstraction. The user of

the program is encouraged to think in a vocabulary that reflects the tasks

for which the program is used, rather than the steps by which the program

does its work. Some of these names are explicitly used to control the

program, either by typing commands or by selecting named choices from a

menu. Our spreadsheet program, for example, uses the name put for the

task of putting a formula into a cell. The algorithm used by the put

command is quite complicated, but the user's picture of the command is

simple. Other names are not explicitly used to control the program;

instead, they give the user a metaphor with which to think

about the work of the program. For example, in describing the operation of

our spreadsheet program, we've talked about rows, columns, cells, and

formulas. Introducing this vocabulary in our program documentation

is just as much an abstraction as introducing new procedures in the program

itself.

In the past we've used procedural abstraction to achieve generalization of an algorithm, moving from specific instances to a more universal capability, especially when we implemented the higher-order functions. If you've used application programs, though, you've probably noticed that in a different sense the abstraction in the program loses generality. For example, a formula in our spreadsheet program can operate only on data that are in cells. The same formula, expressed as a Scheme procedure, can get its arguments from anywhere: from reading a file, from the keyboard, from a global variable, or from the result of invoking some other procedure.

An application program doesn't have to be less general than a programming language. The best application programs are extensible. Broadly speaking, this means that the programmer has made it possible for the user to add capabilities to the program, or modify existing capabilities. This broad idea of extensibility can take many forms in practice. Some kinds of extensibility are more flexible than others; some are easier to use than others. Here are a few examples:

Commercial spreadsheet programs have grown in extensibility. We mentioned that our spreadsheet program allows the user to express a function only as a formula attached to a cell. Modern commercial programs allow the user to define a procedure, similar in spirit to a Scheme procedure, that can then be used in formulas.

Our program, on the other hand, is extensible in a different sense: We provide the Scheme programs that implement the spreadsheet in a form that users can read and modify. In the next chapter, in fact, you'll be asked to extend our spreadsheet. Most commercial programs are provided in a form that computers can read, but people can't. The provision of human-readable programs is an extremely flexible form of extensibility, but not necessarily an easy one, since you have to know how to program to take advantage of it.

We have written much of this book using a home computer as a remote terminal to a larger computer at work. The telecommunication program we're using, called Zterm, has dozens of options. We can set frivolous things like the screen color and the sound used to attract our attention; we can set serious things like the file transfer protocol used to "download" a chapter for printing at home. The program has a directory of telephone numbers for different computers we use, and we can set the technical details of the connection separately for each number. It's very easy to customize the program in all of these ways, because it uses a mouse-driven graphical interface. But the interface is inflexible. For example, although the screen can display thousands of colors, only eight are available in Zterm. More important, if we think of an entirely new feature that would require a modification to the program, there's no way we can do it. This program's extensibility is the opposite of that in our spreadsheet: It's very easy to use, but limited in flexibility.

We started by saying that the abstraction in an application program runs the risk of limiting the program's generality, but that this risk can be countered by paying attention to the goal of extensibility. The ultimate form of extensibility is to provide the full capabilities of a programming language to the user of the application program. This can be done by inventing a special-purpose language for one particular application, such as the Hypertalk language that's used only in the Hypercard application program. Alternatively, the application programmer can take advantage of an existing general-purpose language by making it available within the program. You'll see an example soon, in the database project, which the user controls by typing expressions at a Scheme prompt. The EMACS text editor is a better-known example that includes a Lisp interpreter.

For each of the following exercises, the information to hand in is

the sequence of spreadsheet commands you used to carry out the assignment.

You will find the load command helpful in these exercises.

24.1 Set up a spreadsheet to keep track of the grades in a course. Each column should be an assignment; each row should be a student. The last column should add the grade points from the individual assignments. You can make predictions about your grades on future assignments and see what overall numeric grade each prediction gives you.

24.2 Make a table of tax and tip amounts for a range of possible costs at a

restaurant. Column a should contain the pre-tax amounts, starting at

50 cents and increasing by 50 cents per row. (Do this without entering each

row separately!) Column b should compute the tax, based on your

state's tax rate. Column c should compute the 15% tip. Column d should add columns a through c to get the total cost of the

meal. Column e should contain the same total cost, rounded up to the

next whole dollar amount.

24.3 Make a spreadsheet containing the values from Pascal's triangle: Each

element should be the sum of the number immediately above it and the

number immediately to its left, except that all of column a should have

the value 1, and all of row 1 should have the value 1.

(put (* (cell b) (cell c)) d)

but we aren't going to talk about the details of formulas for a while longer.

Brian Harvey,

bh@cs.berkeley.edu