|

|

A variable is a connection between a name and a value.[1] That sounds simple enough, but some complexities arise in practice. To avoid confusion later, we'll spend some time now looking at the idea of "variable" in more detail.

The name variable comes from algebra. Many people are introduced to variables in high school algebra classes, where the emphasis is on solving equations. "If x3−8=0, what is the value of x?" In problems like these, although we call x a variable, it's really a named constant! In this particular problem, x has the value 2. In any such problem, at first we don't know the value of x, but we understand that it does have some particular value, and that value isn't going to change in the middle of the problem.

In functional programming, what we mean by "variable" is like a named constant in mathematics. Since a variable is the connection between a name and a value, a formal parameter in a procedure definition isn't a variable; it's just a name. But when we invoke the procedure with a particular argument, that name is associated with a value, and a variable is created. If we invoke the procedure again, a new variable is created, perhaps with a different value.

There are two possible sources of confusion about this. One is that you may

have programmed before in a programming language like BASIC or Pascal, in

which a variable often does get a new value, even after it's already

had a previous value assigned to it. Programs in those languages tend to be

full of things like "X = X + 1." Back in Chapter 2 we told

you that this book is about something called

"functional programming," but we haven't yet explained exactly

what that means. (Of course we have introduced a lot of functions,

and that is an important part of it.) Part of what we mean by functional

programming is that once a variable exists, we aren't going to change the value of that variable.

The other possible source of confusion is that in Scheme, unlike the

situation in algebra, we may have more than one variable with the same name

at the same time. That's because we may invoke one procedure, and the body

of that procedure may invoke another procedure, and each of them might use the

same formal parameter name. There might be one variable named x with

the value 7, and another variable named x with the value 51, at the

same time. The pitfall to avoid is thinking "x has changed its value

from 7 to 51."

As an analogy, imagine that you are at a party along with Mick Jagger, Mick Wilson, Mick Avory, and Mick Dolenz. If you're having a conversation with one of them, the name "Mick" means a particular person to you. If you notice someone else talking with a different Mick, you wouldn't think "Mick has become a different person." Instead, you'd think "there are several people here all with the name Mick."

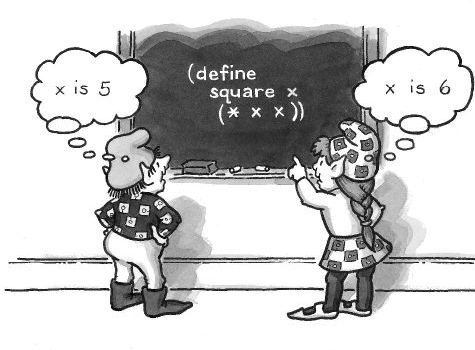

You can understand variables in terms of the

little-people model. A variable, in this model, is the association in the

little person's mind between a formal parameter (name) and the actual

argument (value) she was given. When we want to know (square 5), we

hire Srini and tell him his argument is 5. Srini therefore substitutes 5

for x in the body of square. Later, when we want to know the

square of 6, we hire Samantha and tell her that her argument is 6. Srini and

Samantha have two different variables, both named x.

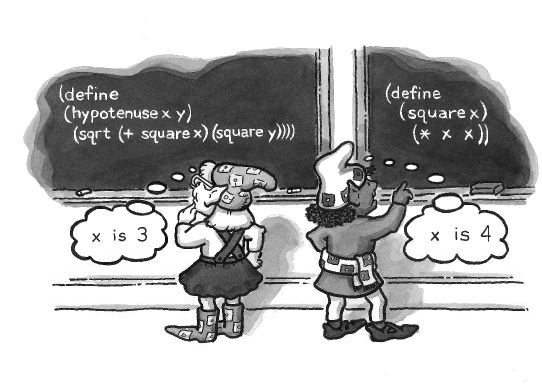

Srini and Samantha do their work separately, one after the other. But

in a more complicated example, there could even be more than

one value called x at the same time:

(define (square x) (* x x)) (define (hypotenuse x y) (sqrt (+ (square x) (square y)))) > (hypotenuse 3 4) 5

Consider the situation when we've hired Hortense to evaluate that

expression. Hortense associates the name x with the value 3 (and also

the name y with the value 4, but we're going to pay attention to x). She has to compute two squares. She hires Solomon to compute

(square 3). Solomon associates the name x with the value 3.

This happens to be the same as Hortense's value, but it's still a separate

variable that could have had a different value—as we see when Hortense

hires Sheba to compute (square 4). Now, simultaneously, Hortense

thinks x is 3 and Sheba thinks x is 4.

(Remember that we said a variable is a connection between a name and a

value. So x isn't a variable! The association of the name x

with the value 5 is a variable. The reason we're being so fussy about this

terminology is that it helps clarify the case in which several variables

have the same name. But in practice people are generally sloppy about this

fine point; we can usually get away with saying "x is a variable"

when we mean "there is some variable whose name is x.")

Another important point about the way little people do variables is that they can't read each others' minds. In particular, they don't know about the values of the local variables that belong to the little people who hired them. For example, the following attempt to compute the value 10 won't work:

(define (f x) (g 6)) (define (g y) (+ x y)) > (f 4) ERROR - VARIABLE X IS UNBOUND.

We hire Franz to compute (f 4). He associates x with

4 and evaluates (g 6) by hiring Gloria. Gloria associates y

with 6, but she doesn't have any value for x, so she's in trouble.

The solution is for Franz to tell Gloria that x is 4:

(define (f x) (g x 6)) (define (g x y) (+ x y)) > (f 4) 10

Until now, we've been using two very different kinds of naming. We have

names for procedures, which are created permanently by define and are

usable throughout our programs; and we have names for procedure arguments,

which are associated with values temporarily when we call a

procedure and are usable only inside that procedure.

These two kinds of naming seem to be different in every way. One is for procedures, one for data; the one for procedures makes a permanent, global name, while the one for data makes a temporary, local name. That picture does reflect the way that procedures and other data are usually used, but we'll see that really there is only one kind of naming. The boundaries can be crossed: Procedures can be arguments to other procedures, and any kind of data can have a permanent, global name. Right now we'll look at that last point, about global variables.

Just as we've been using define to associate names with procedures

globally, we can also use it for other kinds of data:

> (define pi 3.141592654) > (+ pi 5) 8.141592654 > (define song '(I am the walrus)) > (last song) WALRUS

Once defined, a global variable can be used anywhere, just as a defined

procedure can be used anywhere. (In fact, defining a procedure creates a

variable whose value is the procedure. Just as pi is the name of a

variable whose value is 3.141592654, last is the name of a variable

whose value is a primitive procedure. We'll come back to this

point in Chapter 9.) When the name of a global variable

appears in an expression, the corresponding value must be substituted, just

as actual argument values are substituted for formal parameters.

When a little person is hired to carry out a compound procedure, his or her first step is to substitute actual argument values for formal parameters in the body. The same little person substitutes values for global variable names also. (What if there is a global variable whose name happens to be used as a formal parameter in this procedure? Scheme's rule is that the formal parameter takes precedence, but even though Scheme knows what to do, conflicts like this make your program harder to read.)

How does this little person know what values to substitute for global

variable names?

What makes a variable "global" in the little-people model

is that every little person knows its value. You can imagine that

there's a big chalkboard, with all the global definitions written on it, that

all the little people can see.

If you prefer, you could imagine that whenever a global variable is defined,

the define specialist climbs up a huge ladder, picks up a megaphone,

and yells something like "Now hear this! Pi is 3.141592654!"

The association of a formal parameter (a name) with an actual argument (a value) is called a local variable.

It's awkward to have to say "Harry associates the value 7 with the name

foo" all the time. Most of the time we just say "foo has the

value 7," paying no attention to whether this association is in some

particular little person's head or if everybody knows it.

We said earlier in a footnote that Scheme doesn't actually do all the copying and substituting we've been talking about. What actually happens is more like our model of global variables, in which there is a chalkboard somewhere that associates names with values—except that instead of making a new copy of every expression with values substituted for names, Scheme works with the original expression and looks up the value for each name at the moment when that value is needed. To make local variables work, there are several chalkboards: a global one and one for each little person.

The fully detailed model of variables using several chalkboards is what many people find hardest about learning Scheme. That's why we've chosen to use the simpler substitution model.[2]

LetWe're going to write a procedure that solves quadratic equations. (We know this is the prototypical boring programming problem, but it illustrates clearly the point we're about to make.)

We'll use the quadratic formula that you learned in high school algebra class:

(define (roots a b c)

(se (/ (+ (- b) (sqrt (- (* b b) (* 4 a c))))

(* 2 a))

(/ (- (- b) (sqrt (- (* b b) (* 4 a c))))

(* 2 a))))

Since there are two possible solutions, we return a sentence containing two numbers. This procedure works fine,[3] but it does have the disadvantage of repeating a lot of the work. It computes the square root part of the formula twice. We'd like to avoid that inefficiency.

One thing we can do is to compute the square root and use that as the actual argument to a helper procedure that does the rest of the job:

(define (roots a b c)

(roots1 a b c (sqrt (- (* b b) (* 4 a c)))))

(define (roots1 a b c discriminant)

(se (/ (+ (- b) discriminant) (* 2 a))

(/ (- (- b) discriminant) (* 2 a))))

This version evaluates the square root only once. The resulting

value is used as the argument named discriminant in roots1.

We've solved the problem we posed for ourselves initially: avoiding the

redundant computation of the discriminant (the square-root part of the

formula). The cost, though, is that we had to define an auxiliary procedure

roots1 that doesn't make much sense on its own. (That is, you'd never

invoke roots1 for its own sake; only roots uses it.)

Scheme provides a notation to express a computation of this kind more

conveniently. It's called let:

(define (roots a b c)

(let ((discriminant (sqrt (- (* b b) (* 4 a c)))))

(se (/ (+ (- b) discriminant) (* 2 a))

(/ (- (- b) discriminant) (* 2 a)))))

Our new program is just an abbreviation for the previous version:

In effect, it creates a temporary procedure just like roots1, but

without a name, and invokes it with the specified argument value. But the

let notation rearranges things so that we can say, in the right order,

"let the variable discriminant have the value (sqrt&hellip)

and, using that variable, compute the body."

Let is a special form that takes two arguments. The first is

a sequence of name-value pairs enclosed in parentheses. (In this example,

there is only one name-value pair.) The second argument, the body

of the let, is the expression to evaluate.

Now that we have this notation, we can use it with more than one name-value connection to eliminate even more redundant computation:

(define (roots a b c)

(let ((discriminant (sqrt (- (* b b) (* 4 a c))))

(minus-b (- b))

(two-a (* 2 a)))

(se (/ (+ minus-b discriminant) two-a)

(/ (- minus-b discriminant) two-a))))

In this example, the first argument to let includes three

name-value pairs. It's as if we'd defined and invoked a procedure like

the following:

(define (roots1 discriminant minus-b two-a) ...)

Like cond, let uses parentheses both with the usual meaning

(invoking a procedure) and to group sub-arguments that belong together. This

grouping happens in two ways. Parentheses are used to group a name and the

expression that provides its value. Also, an additional pair of parentheses

surrounds the entire collection of name-value pairs.

If you've programmed before in other languages, you may be accustomed to a style of programming in which you change the value of a variable by assigning it a new value. You may be tempted to write

> (define x (+ x 3)) ;; no-no

Although some versions of Scheme do allow such redefinitions, so that you can correct errors in your procedures, they're not strictly legal. A definition is meant to be permanent in functional programming. (Scheme does include other mechanisms for non-functional programming, but we're not studying them in this book because once you allow reassignment you need a more complex model of the evaluation process.)

When you create more than one temporary variable at once using let, all of the expressions that provide the values are computed before any

of the variables are created. Therefore, you can't have one expression

depend on another:

> (let ((a (+ 4 7)) ;; wrong!

(b (* a 5)))

(+ a b))

Don't think that a gets the value 11 and therefore b

gets the value 55. That let expression is equivalent to defining a

helper procedure

(define (helper a b) (+ a b))

and then invoking it:

(helper (+ 4 7) (* a 5))

The argument expressions, as always, are evaluated before

the function is invoked. The expression (* a 5) will be evaluated

using the global value of a, if there is one. If not, an

error will result. If you want to use a in computing b, you

must say

> (let ((a (+ 4 7)))

(let ((b (* a 5)))

(+ a b)))

66

Let's notation is tricky because, like cond, it uses

parentheses that don't mean procedure invocation. Don't teach yourself magic

formulas like "two open parentheses before the let variable and three

close parentheses at the end of its value." Instead, think about the

overall structure:

(let variables body)

Let takes exactly two arguments. The first argument to let is one or more name-value groupings, all in parentheses:

((name1 value1) (name2 value2) (name3 value3) &hellip)

Each name is a single word; each value can be any

expression, usually a procedure invocation. If it's a procedure invocation,

then parentheses are used with their usual meaning.

The second argument to let is the expression to be evaluated using

those variables.

Now put all the pieces together:

(let ((name1 (fn1 arg1))

(name2 (fn2 arg2))

(name3 (fn3 arg3)))

body)

7.1 The following procedure does some redundant computation.

(define (gertrude wd)

(se (if (vowel? (first wd)) 'an 'a)

wd

'is

(if (vowel? (first wd)) 'an 'a)

wd

'is

(if (vowel? (first wd)) 'an 'a)

wd))

> (gertrude 'rose)

(A ROSE IS A ROSE IS A ROSE)

> (gertrude 'iguana)

(AN IGUANA IS AN IGUANA IS AN IGUANA)

Use let to avoid the redundant work.

7.2 Put in the missing parentheses:

> (let pi 3.14159

pie 'lemon meringue

se 'pi is pi 'but pie is pie)

(PI IS 3.14159 BUT PIE IS LEMON MERINGUE)

7.3 The following program doesn't work. Why not? Fix it.

(define (superlative adjective word) (se (word adjective 'est) word))

It's supposed to work like this:

> (superlative 'dumb 'exercise) (DUMBEST EXERCISE)

7.4 What does this procedure do? Explain how it manages to work.

(define (sum-square a b)

(let ((+ *)

(* +))

(* (+ a a) (+ b b))))

[2] The reason that all of our

examples work with the substitution model is that this book uses only

functional programming, in the sense that we never change the value of a

variable. If we started doing the X = X + 1 style of programming, we

would need the more complicated chalkboard model.

[3] That is, it works if the equation has real roots, or if your version of Scheme has complex numbers. Also, the limited precision with which computers can represent irrational numbers can make this particular algorithm give wrong answers in practice even though it's correct in theory.

Brian Harvey,

bh@cs.berkeley.edu