|

|

Note: If you read Part IV before this one, pretend you didn't; we are going to develop a different technique for solving similar problems.

You can use the function first to find the first letter

of a word. What if you want to find the first letters of several words? You

did this in the first chapter, as part of the process of finding acronyms.

To start with a simple case, suppose you have two words (that is, a sentence

of length two). You could apply the first procedure to each of them and

combine the results:

(define (two-firsts sent)

(se (first (first sent))

(first (last sent))))

> (two-firsts '(john lennon))

(J L)

> (two-firsts '(george harrison))

(G H)

Similarly, here's the version for three words:

(define (three-firsts sent)

(se (first (first sent))

(first (first (bf sent)))

(first (last sent))))

> (three-firsts '(james paul mccartney))

(J P M)

But this approach would get tiresome if you had a sentence of five

words—you'd have to write a procedure specifically for the case of exactly

five words, and that procedure would have five separate subexpressions to

extract the first word, the second word, and so on. Also, you don't

want a separate procedure for every sentence length; you want one function

that works no matter how long the sentence is. Using the tools you've

already learned about, the only possible way to do that would be pretty

hideous:

(define (first-letters sent)

(cond ((= (count sent) 1) (one-first sent))

((= (count sent) 2) (two-firsts sent))

((= (count sent) 3) (three-firsts sent))

… and so on …))

But even this won't work because there's no way to say "and so on" in Scheme. You could write a version that works for all sentences up to, let's say, length 23, but you'd be in trouble if someone tried to use your procedure on a 24-word sentence.

Everyfirst to every word in the sentence, no

matter how long the sentence is." Scheme provides a way to do

this:[1]

(define (first-letters sent) (every first sent)) > (first-letters '(here comes the sun)) (H C T S) > (first-letters '(lucy in the sky with diamonds)) (L I T S W D)

Every takes two arguments. The second argument is a sentence, but the

first is something new: a procedure used as an

argument to another procedure.[2] Notice that there are no parentheses around the word first

in the body of first-letters! By now you've gotten accustomed to

seeing parentheses whenever you see the name of a function. But parentheses

indicate an invocation of a function, and we aren't invoking first here. We're using first, the procedure itself, as an argument

to every.

> (every last '(while my guitar gently weeps)) (E Y R Y S) > (every - '(4 5 7 8 9)) (-4 -5 -7 -8 -9)These examples use

every with primitive procedures, but of

course you can also define procedures of your own and apply them to every

word of a sentence:

(define (plural noun)

(if (equal? (last noun) 'y)

(word (bl noun) 'ies)

(word noun 's)))

> (every plural '(beatle turtle holly kink zombie))

(BEATLES TURTLES HOLLIES KINKS ZOMBIES)

You can also use a word as the second argument to every. In this case,

the first-argument procedure is applied to every letter of the word. The

results are collected in a sentence.

(define (double letter) (word letter letter)) > (every double 'girl) (GG II RR LL) > (every square 547) (25 16 49)

In all these examples so far, the first argument to every was a

function that returned a word, and the value returned by every

was a sentence containing all the returned words.

The first argument to every can also be a function that returns a

sentence. In this case, every returns one long sentence:

(define (sent-of-first-two wd)

(se (first wd) (first (bf wd))))

> (every sent-of-first-two '(the inner light))

(T H I N L I)

> (every sent-of-first-two '(tell me what you see))

(T E M E W H Y O S E)

> (define (g wd)

(se (word 'with wd) 'you))

> (every g '(in out))

(WITHIN YOU WITHOUT YOU)

A function that takes another function as one of its arguments, as

every does, is called a higher-order function.

If we focus our attention on procedures, the mechanism through which

Scheme computes functions, we think of every as a procedure

that takes another procedure as an argument—a higher-order

procedure.

Earlier we used the metaphor of the "function machine," with a

hopper at the top into which we throw data, and a chute at the

bottom from which the result falls, like a meat grinder. Well,

every is a function machine into whose hopper we throw another

function machine! Instead of a meat grinder, we have a metal

grinder.[3]

Do you see what an exciting idea this is? We are accustomed to thinking of numbers and sentences as "real things," while functions are less like things and more like activities. As an analogy, think about cooking. The real foods are the meats, vegetables, ice cream, and so on. You can't eat a recipe, which is analogous to a function. A recipe has to be applied to ingredients, and the result of carrying out the recipe is an edible meal. It would seem weird if a recipe used other recipes as ingredients: “Preheat the oven to 350 and insert your Joy of Cooking.” But in Scheme we can do just that.[4]

Cooking your cookbook is unusual, but the general principle isn't. In some contexts we do treat recipes as things rather than as algorithms. For example, people write recipes on cards and put them into a recipe file box. Then they perform operations such as searching for a particular recipe, sorting the recipes by category (main dish, dessert, etc.), copying a recipe for a friend, and so on. The same recipe is both a process (when we're cooking with it) and the object of a process (when we're filing it).

KeepOnce we have this idea, we can use functions of functions to provide many different capabilities.

For instance, the keep function takes a predicate and a sentence as

arguments. It returns a sentence containing only the words of the argument

sentence for which the predicate is true.

> (keep even? '(1 2 3 4 5)) (2 4) > (define (ends-e? word) (equal? (last word) 'e)) > (keep ends-e? '(please put the salami above the blue elephant)) (PLEASE THE ABOVE THE BLUE) > (keep number? '(1 after 909)) (1 909)

Keep will also accept a word as its second argument. In this case, it

applies the predicate to every letter of the word and returns another word:

> (keep number? 'zonk23hey9) 239 > (define (vowel? letter) (member? letter '(a e i o u))) > (keep vowel? 'piggies) IIE

When we used every to select the first letters of words

earlier, we found the first letters even of uninteresting words such

as "the." We're working toward an acronym procedure, and for that

purpose we'd like to be able to discard the boring words.

(define (real-word? wd) (not (member? wd '(a the an in of and for to with)))) > (keep real-word? '(lucy in the sky with diamonds)) (LUCY SKY DIAMONDS) > (every first (keep real-word? '(lucy in the sky with diamonds))) (L S D)

AccumulateIn every and keep, each element of the second argument

contributes independently to the overall result. That is, every and keep apply a procedure to a single element at a time. The

overall result is a collection of individual results, with no interaction

between elements of the argument. This doesn't let us say things like "Add

up all the numbers in a sentence," where the desired output is a function

of the entire argument sentence taken as a whole. We can do this with a

procedure named accumulate. Accumulate takes a procedure and

a sentence as its arguments. It applies that procedure to two of the words

of the sentence. Then it applies the procedure

to the result we got back and another element of the sentence, and so on.

It ends when it's combined all the words of the sentence into a single result.

> (accumulate + '(6 3 4 -5 7 8 9))

32

> (accumulate word '(a c l u))

ACLU

> (accumulate max '(128 32 134 136))

136

> (define (hyphenate word1 word2)

(word word1 '- word2))

> (accumulate hyphenate '(ob la di ob la da))

OB-LA-DI-OB-LA-DA

(In all of our examples in this section, the second argument contains at least two elements. In the "pitfalls" section at the end of the chapter, we'll discuss what happens with smaller arguments.)

Accumulate can also take a word as its second argument, using the

letters as elements:

> (accumulate + 781) 16 > (accumulate sentence 'colin) (C O L I N)

keep the numbers in the sentence, then

we accumulate the result with +. It's easier to say in Scheme:

(define (add-numbers sent) (accumulate + (keep number? sent))) > (add-numbers '(4 calling birds 3 french hens 2 turtle doves)) 9 > (add-numbers '(1 for the money 2 for the show 3 to get ready and 4 to go)) 10

We also have enough tools to write a version of the count procedure,

which finds the number of words in a sentence or the number of letters in a

word. First, we'll define a procedure always-one that returns 1 no

matter what its argument is. We'll every always-one over our argument

sentence,[5] which will result in a sentence of as

many ones as there were words in the original sentence. Then we can use

accumulate with + to add up the ones. This is a slightly

roundabout approach; later we'll see a more natural way to find the count of a sentence.

(define (always-one arg) 1) (define (count sent) (accumulate + (every always-one sent))) > (count '(the continuing story of bungalow bill)) 6You can now understand the

acronym procedure from Chapter 1:

(define (acronym phrase) (accumulate word (every first (keep real-word? phrase)))) > (acronym '(reduced instruction set computer)) RISC > (acronym '(structure and interpretation of computer programs)) SICP

So far you've seen three higher-order functions: every,

keep, and accumulate. How do you decide which one to

use for a particular problem?

Every transforms each element of a word or sentence individually. The

result sentence usually contains as many elements as the

argument.[6]

Keep selects certain elements of a word or sentence and discards the

others. The elements of the result are elements of the argument, without

transformation, but the result may be smaller than the original.

Accumulate transforms the entire word or sentence into a single result

by combining all of the elements in some way.

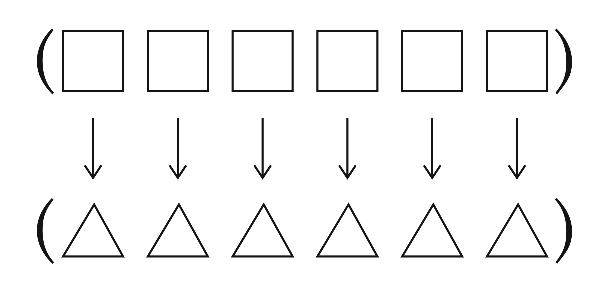

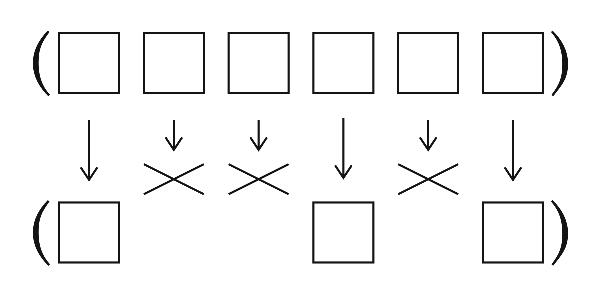

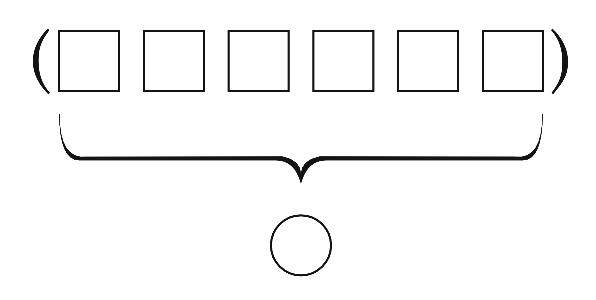

These three pictures represent graphically the differences in the meanings

of every, keep, and accumulate. In the pictures, we're

applying these higher-order procedures to sentences, but don't forget that

we could have drawn similar pictures in which the higher-order procedures

process the letters of a word.

Here's another way to compare these three higher-order functions:

| function | purpose | first argument is a … |

|---|---|---|

every | transform | one-argument transforming function |

keep | select | one-argument predicate function |

accumulate | combine | two-argument combining function |

To help you understand these differences, we'll look at specific examples

using each of them, with each example followed by an equivalent computation

done without the higher-order procedure. Here is an example for every:

> (every double 'girl)

(GG II RR LL)

> (se (double 'g)

(double 'i)

(double 'r)

(double 'l))

(GG II RR LL)

You can, if you like, think of the first of these expressions as abbreviating the second.

An expression using keep can also be replaced with an expression that

performs the same computation without using keep. This time it's a

little messier:

> (keep even? '(1 2 3 4 5))

(2 4)

> (se (if (even? 1) 1 '())

(if (even? 2) 2 '())

(if (even? 3) 3 '())

(if (even? 4) 4 '())

(if (even? 5) 5 '()))

(2 4)

Here's how an accumulate can be expressed the long way:

> (accumulate word '(a c l u)) ACLU > (word 'a (word 'c (word 'l 'u))) ACLU

(Of course word will accept any number of arguments, so we

could have computed the same result with all four letters as arguments to

the same invocation. But the version we've shown here indicates how

accumulate actually works; it combines the elements one by one.)

If Scheme (or any dialect of Lisp) is your first programming language,

having procedures that operate on entire sentences at once may not seem like

a big deal. But if you used to program in some lesser language, you're

probably accustomed to writing something like first-letters as a loop in which you have some variable named I and you carry out some

sequence of steps for I=1, I=2, and so on, until you get to N, the number of elements. The use of higher-order functions allows us to

express this problem all at once, rather than as a sequence of events. Once

you're accustomed to the Lisp way of thinking, you can tell yourself "just

take every first of the sentence," and that feels like a single step,

not a complicated task.

Two aspects of Scheme combine to permit this mode of expression. One, which we've mentioned earlier, is that sentences are first-class data. You can use an entire sentence as an argument to a procedure. You can type a quoted sentence in, or you can compute a sentence by putting words together.

The second point is that functions are also first-class. This lets us write

a procedure like pigl that applies to a single word, and then

combine that with every to translate an entire sentence to Pig Latin.

If Scheme didn't have first-class functions, we couldn't have general-purpose

tools like keep and every, because we couldn't say which

function to extend to all of a sentence. You'll see later that without every it would still be possible to write a specific pigl-sent

procedure and separately write a first-letters procedure. But the

ability to use a procedure as argument to another procedure lets us generalize the idea of "apply this function to every word of the

sentence."

RepeatedAll the higher-order functions you've seen so far take functions as arguments, but none of them have functions as return values. That is, we have machines that can take machines in their input hoppers, but now we'd like to think about machines that drop other machines out of their output chutes—machine factories, so to speak.

In the following example, the procedure repeated returns a procedure:

> ((repeated bf 3) '(she came in through the bathroom window))

(THROUGH THE BATHROOM WINDOW)

> ((repeated plural 4) 'computer)

COMPUTERSSSS

> ((repeated square 2) 3)

81

> (define (double sent)

(se sent sent))

> ((repeated double 3) '(banana))

(BANANA BANANA BANANA BANANA BANANA BANANA BANANA BANANA)

The procedure repeated takes two arguments, a procedure and a number,

and returns a new procedure. The returned procedure is one that invokes the

original procedure repeatedly. For example, (repeated bf 3)

returns a function that takes the butfirst of the butfirst of the

butfirst of its argument.

Notice that all our examples start with two open parentheses. If we just

invoked repeated at the Scheme prompt, we would get back a procedure,

like this:

> (repeated square 4) #<PROCEDURE>The procedure that we get back isn't very interesting by itself, so we invoke it, like this:

> ((repeated square 4) 2) 65536To understand this expression, you must think carefully about its two subexpressions. Two subexpressions? Because there are two open parentheses next to each other, it would be easy to ignore one of them and therefore think of the expression as having four atomic subexpressions. But in fact it has only two. The first subexpression,

(repeated square 4), has a procedure as its value. The second

subexpression, 2, has a number as its value. The value of the entire

expression comes from applying the procedure to the number.

All along we've been saying that you evaluate a compound expression in two

steps: First, you evaluate all the subexpressions. Then you apply the

first value, which has to be a procedure, to the rest of the values. But

until now the first subexpression has always been just a single word, the

name of a procedure. Now we see that the first expression might be an

invocation of a higher-order function, just as any of the argument

subexpressions might be function invocations.

We can use repeated to define item, which returns a particular

element of a sentence:

(define (item n sent) (first ((repeated bf (- n 1)) sent))) > (item 1 '(a day in the life)) A > (item 4 '(a day in the life)) THE

Some people seem to fall in love with every and try to use it in

all problems, even when keep or accumulate would be more

appropriate.

If you find yourself using a predicate function as the first argument to

every, you almost certainly mean to use keep instead. For

example, we want to write a procedure that determines whether any of the

words in its argument sentence are numbers:

(define (any-numbers? sent) ;; wrong! (accumulate or (every number? sent)))

This is wrong for two reasons. First, since Boolean values aren't words, they can't be members of sentences:

> (sentence #T #F) ERROR: ARGUMENT TO SENTENCE NOT A WORD OR SENTENCE: #F > (every number? '(a b 2 c 6)) ERROR: ARGUMENT TO SENTENCE NOT A WORD OR SENTENCE: #T

Second, even if you could have a sentence of Booleans, Scheme doesn't allow

a special form, such as or, as the argument to a higher-order

function.[7] Depending on your version of Scheme,

the incorrect any-numbers? procedure might give an error message about

either of these two problems.

Instead of using every, select the numbers from the argument and count

them:

(define (any-numbers? sent) (not (empty? (keep number? sent))))

The keep function always returns a result of the same type (i.e.,

word or sentence) as its second argument. This makes sense because if you're

selecting a subset of the words of a sentence, you want to end up with a

sentence; but if you're selecting a subset of the letters of a word, you

want a word. Every, on the other hand, always returns a sentence.

You might think that it would make more sense for every to return a

word when its second argument is a word. Sometimes that is what you

want, but sometimes not. For example:

(define (spell-digit digit) (item (+ 1 digit) '(zero one two three four five six seven eight nine))) > (every spell-digit 1971) (ONE NINE SEVEN ONE)

In the cases where you do want a word, you can just accumulate word the sentence that every returns.

Remember that every expects its first argument to be a function of

just one argument. If you invoke every with a function such as quotient, which expects two arguments, you will get an error message from

quotient, complaining that it only got one argument and wanted to get

two.

Some people try to get around this by saying things like

(every (quotient 6) '(1 2 3)) ;; wrong!

This is a sort of wishful thinking. The intent is that Scheme

should interpret the first argument to every as a fill-in-the-blank

template, so that every will compute the values of

(quotient 6 1) (quotient 6 2) (quotient 6 3)

But of course what Scheme really does is the same thing it always

does: It evaluates the argument expressions, then invokes every. So

Scheme will try to compute (quotient 6) and will give an error message.

We picked quotient for this example because it requires exactly two

arguments. Many Scheme primitives that ordinarily take two arguments,

however, will accept only one. Attempting the same wishful thinking with

one of these procedures is still wrong, but the error message is different.

For example, suppose you try to add 3 to each of several numbers this way:

(every (+ 3) '(1 2 3)) ;; wrong!

The first argument to every in this case isn't "the

procedure that adds 3," but the result returned by invoking + with

the single argument 3. (+ 3) returns the number 3, which

isn't a procedure. So you will get an error message like "Attempt to apply

non-procedure 3."

The idea behind this mistake—looking for a way to "specialize" a two-argument procedure by supplying one of the arguments in advance—is actually a good one. In the next chapter we'll introduce a new mechanism that does allow such specialization.

If the procedure you use as the argument to every returns an empty

sentence, then you may be surprised by the results:

(define (beatle-number n)

(if (or (< n 1) (> n 4))

'()

(item n '(john paul george ringo))))

> (beatle-number 3)

GEORGE

> (beatle-number 5)

()

> (every beatle-number '(2 8 4 0 1))

(PAUL RINGO JOHN)

What happened to the 8 and the 0? Pretend that every didn't exist, and you had to do it the hard way:

(se (beatle-number 2) (beatle-number 8) (beatle-number 4)

(beatle-number 0) (beatle-number 1))

Using result replacement, we would get

(se 'paul '() 'ringo '() 'john)

which is just (PAUL RINGO JOHN).

On the other hand, if every's argument procedure returns an empty word, it will appear in the result.

> (every bf '(i need you))

("" EED OU)

The sentence returned by every has three words in it: the

empty word, eed, and ou.

Don't confuse

(first '(one two three four))

with

(every first '(one two three four))

In the first case, we're applying the procedure first to a

sentence; in the second, we're applying first four separate times,

to each of the four words separately.

What happens if you use a one-word sentence or one-letter word as argument

to accumulate? It returns that word or that letter, without even

invoking the given procedure. This makes sense if you're using something

like + or max as the accumulator, but it's disconcerting that

(accumulate se '(one-word))

returns the word one-word.

What happens if you give accumulate an empty sentence or word?

Accumulate accepts empty arguments for some combiners, but not for

others:

> (accumulate + '()) 0 > (accumulate max '()) ERROR: CAN'T ACCUMULATE EMPTY INPUT WITH THAT COMBINER

The combiners that can be used with an empty sentence or word are

+, *, word, and sentence. Accumulate checks

specifically for one of these combiners.

Why should these four procedures, and no others, be allowed to accumulate an empty sentence or word? The difference between these and

other combiners is that you can invoke them with no arguments, whereas max, for example, requires at least one number:

> (+) 0 > (max) ERROR: NOT ENOUGH ARGUMENTS TO #<PROCEDURE>.

Accumulate actually invokes the combiner with no arguments

in order to find out what value to return for an empty sentence or word.

We would have liked to implement accumulate so that any

procedure that can be invoked with no arguments would be accepted as a

combiner to accumulate the empty sentence or word. Unfortunately, Scheme

does not provide a way for a program to ask, "How many arguments will this

procedure accept?" The best we could do was to build a particular set of

zero-argument-okay combiners into the definition of accumulate.

Don't think that the returned value for an empty argument is always zero or empty.

> (accumulate * '()) 1

The explanation for this behavior is that any function that works

with no arguments returns its identity element in that case.

What's an identity element? The function + has the identity element

0 because (+ anything 0) returns the anything. Similarly, the empty word is the identity element for word. In general, a function's identity element has the property that when

you invoke the function with the identity element and something else as

arguments, the return value is the something else. It's a Scheme convention

that a procedure with an identity element returns that element when invoked

with no arguments.[8]

The use of two consecutive open parentheses to invoke the procedure returned by a procedure is a strange-looking notation:

((repeated bf 3) 987654)

Don't confuse this with the similar-looking cond notation,

in which the outer parentheses have a special meaning (delimiting a cond clause). Here, the parentheses have their usual meaning. The inner

parentheses invoke the procedure repeated with arguments bf and

3. The value of that expression is a procedure. It doesn't have a

name, but for the purposes of this paragraph let's pretend it's called bfthree. Then the outer parentheses are basically saying (bfthree 987654); they apply the unnamed procedure to the argument 987654.

In other words, there are two sets of parentheses because there are two

functions being invoked: repeated and the function returned by

repeated. So don't say

(repeated bf 3 987654) ;; wrong

just because it looks more familiar. Repeated isn't a

function of three arguments.

8.1 What does Scheme return as the value of each of the following expressions? Figure it out for yourself before you try it on the computer.

> (every last '(algebra purple spaghetti tomato gnu)) > (keep number? '(one two three four)) > (accumulate * '(6 7 13 0 9 42 17)) > (member? 'h (keep vowel? '(t h r o a t))) > (every square (keep even? '(87 4 7 12 0 5))) > (accumulate word (keep vowel? (every first '(and i love her)))) > ((repeated square 0) 25) > (every (repeated bl 2) '(good day sunshine))

8.2 Fill in the blanks in the following Scheme interactions:

> (______ vowel? 'birthday) IA > (______ first '(golden slumbers)) (G S) > (______ '(golden slumbers)) GOLDEN > (______ ______ '(little child)) (E D) > (______ ______ (______ ______ '(little child))) ED > (______ + '(2 3 4 5)) (2 3 4 5) > (______ + '(2 3 4 5)) 14

8.3 Describe each of the following functions in English. Make sure to include a description of the domain and range of each function. Be as precise as possible; for example, "the argument must be a function of one numeric argument" is better than "the argument must be a function."

(define (f a) (keep even? a)) (define (g b) (every b '(blue jay way)))

(define (h c d) (c (c d))) (define (i e) (/ (accumulate + e) (count e))) accumulate sqrt repeated (repeated sqrt 3) (repeated even? 2) (repeated first 2) (repeated (repeated bf 3) 2)

Note: Writing helper procedures may be useful in solving some of these

problems. If you read Part IV before this, do not use recursion

in solving these problems; use higher order functions instead.

8.4 Write a procedure

8.5 Write a procedure

8.6 When you're talking to someone over a noisy radio connection, you sometimes

have to spell out a word in order to get the other person to understand it.

But names of letters aren't that easy to understand either, so there's a

standard code in which each letter is represented by a particular word that

starts with the letter. For example, instead of "B" you say "bravo."

Write a procedure (You may make up your own names for the letters or look up the

standard ones if you want.)

Hint: Start by writing a helper procedure that figures out the name for a

single letter.

8.7 [14.5][9]

Write a procedure

8.8 [12.5]

Write an It should double all the numbers in the sentence, and it should replace

"good" with "great," "bad" with "terrible," and anything else you

can think of.

8.9 What procedure can you use as the first argument to What procedure can you use as the first argument to What procedure can you use as the first argument to

8.10 Write a predicate

8.11 [12.6]

Write a GPA procedure. It should take a sentence of grades as its argument

and return the corresponding grade point average:

Hint: write a helper procedure

8.12 [11.2]

When you teach a class, people will get distracted if you say "um" too many

times. Write a

8.13 [11.3]

Write a procedure

8.14 Write the procedure

choose-beatles that takes a predicate

function as its argument and returns a sentence of just those Beatles (John,

Paul, George, and Ringo) that satisfy the predicate. For example:

(define (ends-vowel? wd) (vowel? (last wd)))

(define (even-count? wd) (even? (count wd)))

> (choose-beatles ends-vowel?)

(GEORGE RINGO)

> (choose-beatles even-count?)

(JOHN PAUL GEORGE)

transform-beatles that takes a procedure as an

argument, applies it to each of the Beatles, and returns the results in a

sentence:

(define (amazify name)

(word 'the-amazing- name))

> (transform-beatles amazify)

(THE-AMAZING-JOHN THE-AMAZING-PAUL THE-AMAZING-GEORGE

THE-AMAZING-RINGO)

> (transform-beatles butfirst)

(OHN AUL EORGE INGO)

words that takes a word as its argument and

returns a sentence of the names of the letters in the word:

> (words 'cab)

(CHARLIE ALPHA BRAVO)

letter-count that takes a sentence as its

argument and returns the total number of letters in the sentence:

> (letter-count '(fixing a hole))

11

exaggerate procedure which exaggerates sentences:

> (exaggerate '(i ate 3 potstickers))

(I ATE 6 POTSTICKERS)

> (exaggerate '(the chow fun is good here))

(THE CHOW FUN IS GREAT HERE)

every so that for

any sentence used as the second argument, every returns that sentence?

keep so that for

any sentence used as the second argument, keep returns that sentence?

accumulate so that

for any sentence used as the second argument, accumulate returns that

sentence?

true-for-all? that takes two arguments, a

predicate procedure and a sentence. It should return #t if the

predicate argument returns true for every word in the sentence.

> (true-for-all? even? '(2 4 6 8))

#T

> (true-for-all? even? '(2 6 3 4))

#F

> (gpa '(A A+ B+ B))

3.67

base-grade that takes

a grade as argument and returns 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4, and another helper

procedure grade-modifier that returns −.33, 0, or .33, depending on

whether the grade has a minus, a plus, or neither.

count-ums that counts the number of times "um"

appears in a sentence:

> (count-ums

'(today um we are going to um talk about functional um programming))

3

phone-unspell that takes a spelled version of

a phone number, such as POPCORN, and returns the real phone number, in

this case 7672676. You will need to write a helper procedure that

uses an 8-way cond expression to translate a single letter into a

digit.

subword that takes three arguments: a

word, a starting position number, and an ending position number. It should

return the subword containing only the letters between the specified

positions:

> (subword 'polythene 5 8)

THEN

[1] Like all the procedures in this book that deal with words and

sentences, every and the other procedures in this chapter

are part of our extensions to Scheme. Later, in Chapter 17, we'll

introduce the standard Scheme equivalents.

[2] Talking about every strains our

resolve to distinguish functions from the procedures that implement them.

Is the argument to every a function or a procedure? If we think of

every itself as a procedure—that is, if we're focusing on how it

does its job—then of course we must say that it does its job by repeatedly

invoking the procedure that we supply as an argument. But it's

equally valid for us to focus attention on the function that the every

procedure implements, and that function takes functions as

arguments.

[3] You can get in trouble mathematically by trying to define a function whose domain includes all functions, because applying such a function to itself can lead to a paradox. In programming, the corresponding danger is that applying a higher-order procedure to itself might result in a program that runs forever.

[4] Some recipes may seem to include other recipes, because they say things like "add pesto (recipe on p. 12)." But this is just composition of functions; the result of the pesto procedure is used as an argument to this recipe. The pesto recipe itself is not an ingredient.

[5] We mean, of course, "We'll invoke every with the

procedure always-one and our argument sentence as its two arguments."

After you've been programming computers for a while, this sort of abuse of

English will come naturally to you.

[6] What we mean by "usually" is that every is most

often used with an argument function that returns a single word. If the

function returns a sentence whose length might not be one, then the number

of words in the overall result could be anything!

[7] As we said in Chapter 4, special forms aren't procedures, and aren't first-class.

[8] PC Scheme returns zero for an invocation of max with no arguments, but that's the wrong answer. If anything, the

answer would have to be −∞.

[9] Exercise 14.5 in Part IV asks you to solve this same problem using recursion. Here we are asking you to use higher-order functions. Whenever we pose the same problem in both parts, we'll cross-reference them in brackets as we did here. When you see the problem for the second time, you might want to consult your first solution for ideas.

Brian Harvey,

bh@cs.berkeley.edu